Established 2002

Lucinda Shepherd, friend Robert Randell and various experts for their support.

Coastline features and processes

View west from Kimmeridge in Dorset towards the dramatic coastline at Tyneham.

Coastlines are a complex, ever changing environment, controlled by constructive and destructive forces that shape and alter the characteristics of the landscape. An understanding of the present day features and processes provides a valuable insight into the comparable forces that have occurred for millions of years. Those studying palaeontology will also find a knowledge of coastal features greatly assists their interpretation of scientific literature and enables them to locate productive fossil collecting grounds.

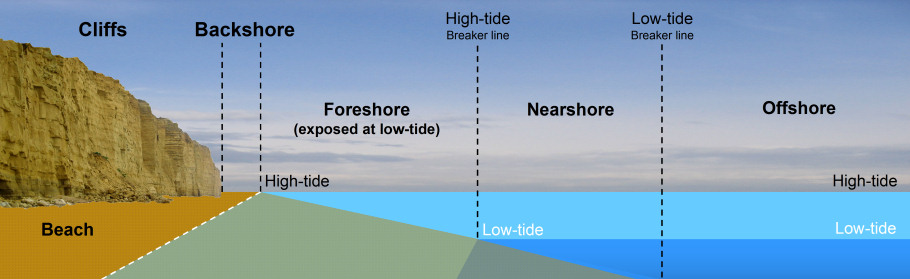

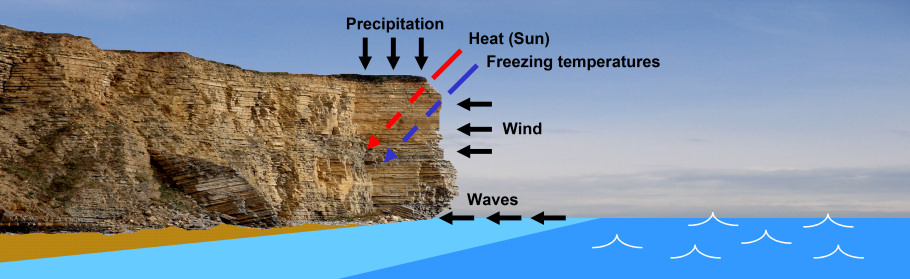

Figure 1: Diagram

showing the basic features of the coast.

Figure 1 above illustrates some of the common features present on a rocky/cliff section of coast, in particular the backshore and foreshore where fossils are more easily collected. Accessibility is often dependent on a low-tide, which occurs every 12 hours approximately. An example of a typical tidal cycle throughout a day would be: Low (6:30am), High (12:45pm), Low (7:00pm), High (1:15am). Tidal cycles are driven by the gravitational pull of the sun and moon on the earth's oceans/seas, and amplified on a local basis by the prevailing weather conditions.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING FOSSILS

Foreshore

Left: Foreshore

exposed at Peacehaven in East Sussex. Right:

Foreshore exposed at

Warden's Point on the Isle of Sheppey.

The distance between high and low-tide exposes an area of the beach known as the foreshore (figure 1); provided neither seaweed nor shingle accumulations are present, these wave swept expanses can expose fossils in situ. As the waves and shingle scour the foreshore, the situ rock is weathered away, leaving the harder fossil remains protruding from the surface.

Left: A small

pyritised ammonite within the foreshore at

Charmouth.

Right: A flint echinoid within the foreshore at

Peacehaven.

The photos above show a small pyritised ammonite (left) exposed on the foreshore at Charmouth and an echinoid (right) preserved as flint at Peacehaven. Over the years some spectacular discoveries have been made along the foreshores of the British Isles, including complete marine reptile skeletons and giant ammonites measuring 6 feet across!

Left: Two limpets

awaiting the incoming tide. Right: Four winkles

neighbouring a sea anemone.

The foreshore also accommodates rock pools, which are home to a wealth of marine life; the photos above show two Limpets clinging to an exposed boulder (left) and a collection of winkles neighbouring a sea anemone (right). In many areas along the British coast the foreshore is considered a zone of geological and/or biological importance, and assigned a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). Where a SSSI exists, visitors are expected to show additional respect for the area, it's usually illegal to remove fossils from the foreshore (and cliffs) in these areas. Discovering Fossils includes a notice within the location summary on each of the relevant fossil locations, alerting readers to SSSI status.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING

FOSSILS

Backshore

Left: Boulders on

the backshore at

Kimmeridge in Dorset. Right:

Fallen slabs and shingle accumulations on the backshore at

Seatown in Dorset.

Located between the high-water mark and the cliff or land is an area known as the backshore (figure 1); this zone does not support marine-life, as it spends the majority of its time above sea-level. The backshore is an important fossil collecting ground, provided a safe distance can be maintained from the cliff (if applicable - see below). Large accumulations of fallen rocks and scree commonly form at the base of tall cliffs, providing an opportunity to find freshly exposed specimens. Please note, within cliff areas the backshore is the most dangerous shore zone; large rocks (as pictured above) can and do fall without warning. Further information about cliffs can be read below.

Cliffs

Cliffs at

Burton Bradstock tower

above the beach; collapses on to the backshore occur frequently

throughout the year, particularly during the winter months.

A cliff is a vertical or near-vertical rock face, typically comprised of exposed situ rock and capped with present day/recent soils. The majority of cliffs occur naturally where the land meets the sea (figure 1), in particular when the coast is composed of denser rock types that are less liable to slumping.

Cliffs are formed by a number of processes, in particular the explosive energy released from waves (and stones carried within them) crashing into their base, the result of which leads to undercutting and eventual collapse of the overlying rock. Figure 2 below illustrates the process of undercutting; a large portion of the cliff base has been eroded and the overlying rock sits precariously above.

Figure 2: A diagram

illustrating the forces that lead to cliff formation.

Other factors contributing to cliff formation include precipitation (rain/snow/hail), which penetrates the natural cracks and fissures throughout the cliff, washing away and/or dissolving less resistant rock and weakening the stability of the cliff. The rate of erosion is accelerated by the freeze-and-thaw action during the winter months, during which time the expanding ice cracks the rock further, notably on the exposed outer surface. Erosion also occurs during the summer months, at which time the cliff is warmed and the evaporating water causes the sediment to contract and crack (porous rock only).

As a result of the forces outlined above, cliffs are constantly changing and on the retreat; inevitably rock falls and large scale collapses occur unpredictably throughout the year.

Left: A boulder

weighing in excess of a tonne lies imbedded in the shingle on the

backshore. Right: A cliff fall leaves many tonnes

of rock on the backshore.

Some of the most dangerous cliff localities in the UK include Kimmeridge, Charmouth, Lyme Regis in Dorset and Port Mulgrave in Yorkshire. We strongly recommend visitors keep a safe distance from the cliff base, usually at least 8 meters; however if your activities require that you pass close to the cliff, then a hard hat is recommended.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Left: A birthday party with

a twist - fossil hunting at

Peacehaven.

Right: A family hold their prized ammonite fossil at Beachy Head.

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it's your first time fossil hunting or you're looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more CLICK HERE