Established 2002

Lucinda Shepherd, friend Robert Randell and various experts for their support.

Seatown (Dorset)

Click above to view page as a PDF.

Click here to download PDF software.

Introduction

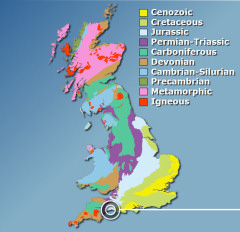

Seatown is a small coastal village located 3 miles east of Charmouth and a short distance from its more famous neighbour Lyme Regis. The cliffs and foreshore date predominantly from the Early Jurassic period, around 189-184 million years ago, and are a younger continuation of the rock sequence seen at Charmouth. Parking and refreshments are available at the beach access point (pictured below); a daily parking charge is payable for much of the year.

From the car park visitors can find fossils in both directions along the beach, although the volume and quality tends to be greatest towards Charmouth in the west (below-left). Provided the tide is falling when you set off from Seatown it's usually possible to walk to and from Charmouth in a single day.

Left: View west

from Thorncombe Beacon towards Seatown and Golden Cap.

Right: Parking is available opposite the Anchor Inn at

Seatown.

Fossils can be found all year round, although the volume significantly increases after periods of heavy rain and stormy conditions. During the summer months and after periods of dry weather fossil collecting can be less productive without prior experience. The most commonly found fossils are belemnite guards and ammonite shells, many of which appear in situ on the sea weathered foreshore; a large number of fossils can also be found loose on the foreshore and are easily collected.

Important: The coastline at Seatown has been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and belongs to the Jurassic Coast - World Heritage Site. Due to its scientific importance there are rules governing the collection of fossils. Visitors can collect loose fossils among the pebbles and from the boulders on the foreshore, however hammering directly into the cliff or foreshore is not permitted.

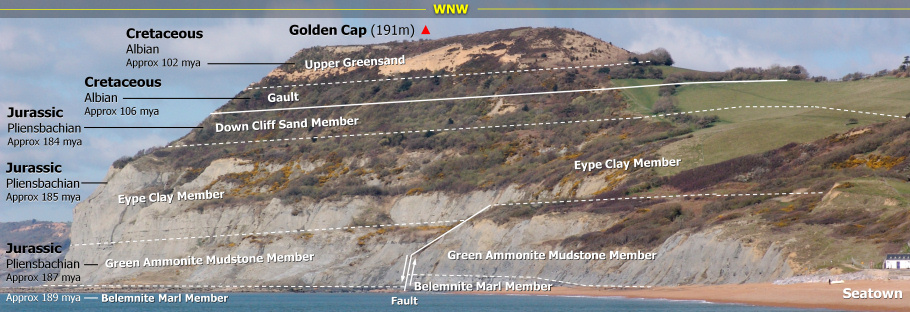

The geology of Seatown (west, towards Charmouth)

To the west of Seatown the cliffs and foreshore beneath Golden Cap date predominantly from the Pliensbachian stage of Early Jurassic period, approximately 189-184 million years ago. During this time a shallow epicontinental sea (less than 100m deep) was present across much of Europe, including most of England, Wales and Ireland, and laid down alternating layers of clay and limestone. At that time, Seatown (as it's now known), lay closer to the equator, roughly at the latitude North Africa is today. Overlying the Jurassic sediments are younger Cretaceous deposits, comprising the Gault and the golden coloured Upper Greensand (green when freshly split) - deposited between 106-102 million years ago (fig.1 below).

Figure 1: View of

Golden Cap from the base of Thorncombe Beacon, showing the locations of the key

geologic horizons.

Fossils can be found throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous exposures, however it's the Jurassic rocks in particular that attract fossil hunters to Seatown.

Life was rich and diverse during the Jurassic period, giant marine reptiles inhabited the seas and pterosaurs flew across the skies. This was also the time of the dinosaurs, however the presence of sea over the area and distance from any significant landmass at the time, means their fossils are rarely found between Seatown and Lyme Regis.

Green Ammonite Mudstone Member: The first rocks encountered west of Seatown belong to the Green Ammonite Mudstone Member, a blue-grey mudstone with limestone bands and scattered nodules (fig.2 and 3 below). The member measures 34 metres from its base (above the Belemnite Marl Member) to the overlying Eype Clay Member. The name 'Green Ammonite' is given to describe the green calcite crystals contained within many of the fossilised ammonites (mostly from the lowest 6m of the member).

Figure 2: Looking

east, the Green Ammonite Mudstone Member is present at beach level

between Seatown and Golden Cap. Figure 3:

Close-up.

The mudstone has little resistance to the force of the sea which erodes its base throughout the year, resulting in near-vertical cliffs that extend to Golden Cap. The process or erosion is accelerated by the soft nature of the mudstone, that slumps under its own weight and pressure from the overlying rocks. The gradual movement associated with the recent slumping is clearly seen by the many contortions in the cliff face.

The mudstone contains an abundance of ammonites including species of Aegoceras, Oistoceras, Liparoceras, Tragophylloceras and Androgynoceras. Preservation of the outer shell chamber is typically good, however most have crushed or missing centres. The cause of this characteristic is the absence of sediment throughout the entire shell during the early stages of fossilisation. As the weight of the overlying sediment exerted pressure on the ammonite shell, the outer chamber (containing sediment) was able to withstand crushing, whereas the unfilled inner chambers became compressed and distorted.

Belemnites, bivalves and marine reptile skeletons can also be found throughout the member. Among the most robustly preserved fossils are found within limestone nodules that appear sporadically throughout the mudstone. These hard, paler coloured nodules frequently contain ammonites protruding from their surface and on some occasions marine reptile bones and teeth, in particular those belonging to ichthyosaurs (see fossil photos towards the end of this page).

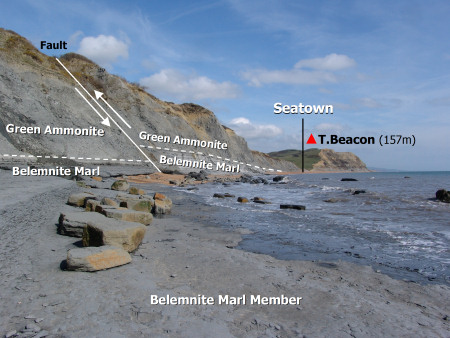

Belemnite Marl Member: Continuing west from Seatown a prominent layer of limestone emerges from the foreshore shingle approximately 200m from the beach access point (fig.4 below). This pale limestone bed represents the top of the Belemnite Marl Member and is one of many characteristically paler layers that together measure 23m in depth. The different shades of grey are the result of the differing organic carbon content (higher in the darker bands).

Figure 4: The

Belemnite Marl Member descends below beach level 200m west of

Seatown. Figure 5: The Belemnite Marls dominate

the foreshore.

Seatown provides the only opportunity to view the Belemnite Marl Member at beach level; at Charmouth and Lyme Regis it appears higher up the cliff face and is largely inaccessible. The upper surface of the member is characterised by a large number of fossilised belemnite guards which protrude horizontally in situ (See fig.5 above and fossil photos below). Despite the name given to the Belemnite Marl Member, ammonites, bivalves, and marine reptile and fish skeletons are also present throughout the member, although in far lesser numbers.

The geology of Seatown (east, towards Thorncombe Beacon)

Despite the close proximity of the cliffs either side of Seatown, the Green Ammonite Mudstone Member (described above) is only visible in the west and does not appear at beach level beyond the small stream that runs along the small valley. Local faulting of the land has forced the rocks to the east downwards, obscuring the Green Ammonite Mudstone Member and bringing the overlying Eype Clay Member to beach level.

![]()

Figure 6: Diagram

showing the approximate locations of the key geologic horizons

beneath Thorncombe Beacon.

Eype Clay Member: This silty mudstone is immediately visible in the cliff face travelling east from Seatown and measures approximately 60m from its base (above the Green Ammonite Mudstone Member) to the overlying Down Cliff Sand Member. The member extends continuously from Seatown, beneath Thorncombe Beacon and beyond to Eype village, although in places is obscured beneath slipped material from the overlying rocks. Ammonites, crinoids, brachiopods and benthic fauna are common throughout the member.

Figure 7: Eype Clay

present at beach level east of Seatown. Right: The

Eype Nodule Bed, visible in the cliff east of Seatown.

A distinctive band of spherical nodules appears midway up the cliff face, marking the aptly named Eype Nodule Bed (above-right).

Down Cliff Sand Member: Overlying the Eype Clay Member is a famous fine-grained sandstone known as the Eype Starfish Bed, belonging to the lowest part of the Down Cliff Sand Member. Its name reflects the number of well preserved starfish recovered from fallen sections of the bed over the centuries. The Starfish Bed also contains brittle stars as pictured below.

Left: Brittle star

(Palaeocoma) Eype Starfish Bed. These specimens have been

carefully exposed using an

air-abrasive tool. Right: Close-up.

The Down Cliff Sand Member consists mainly of grey-brown sandy mudstones, becoming more sandy towards the top; the member measures 30m from its base to the Thorncombe Sand Member above (fig.6 above).

Thorncombe Sand Member: This member lies above the Down Cliff Sand and measures around 30m upwards into the overlying Down Cliff Clay Member. The Thorncombe Sand Member is more yellow-weathered than the Down Cliff Sand Member. This is the uppermost conspicuous horizon within the cliff face shown in fig.6 above. Although visible just a short distance from Seatown, the Thorncombe Sand and overlying members/formations are best observed from the neighbouring village of Eype, and are not the subject of this Seatown page.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING FOSSILS

Where to look for fossils?

Fossils can be found throughout the Jurassic mudstone and limestone beneath Golden Cap in the west and Thorncombe Beacon in the east. Due to the expanse of time encompassed within the rock sequence and the nature of deposition, the fossils differ depending where you look. Generally speaking the rocks become increasingly younger towards the east, changing from fine grey mudstones to grainy yellow sands.

Left: Bill and

Louis search for loose fossils among the foreshore shingle.

Right: Roy and Louis hammer a foreshore boulder in search

of fossils.

For beginners and first time visitors the best place to begin is west of Seatown, towards Charmouth (pictured above). The highly fossiliferous and rapidly eroding cliffs ensure a fresh supply of material on the beach throughout the year, especially during the winter months. This stretch of coast also yields plenty of loose fossils among the shingle, in particular pyritised ammonites, crinoids and belemnites (see fossil photos below).

Left: Small

fossils: (a) regular echinoid, (b) belemnite guards, (c) crinoid

fragments, (d) brachiopods, (e) ammonites, (f) gastropod.

Right: Echinoid close-up.

The specimens pictured above were found among the shingle in about 30 minutes; it's most likely that they all originate from the Belemnite Marl and Green Ammonite Mudstone Members. The regular echinoid (top-left) measures just 6mm in diameter and is much less common than the ammonites and crinoid fragments.

As with all coastal locations, a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download a free trial click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

What fossils might you find?

The most common fossils at Seatown are belemnite guards and ammonite shells, other finds include reptile and fish skeletons, crinoids and bivalve shells. The range of marine fossils reveals a complex prehistoric environment, rich in predators and prey of all sizes. During a single visit it's usually possible to find fragments of each of the specimens that follow, although marine reptile skeletons occur less frequently.

Left: A selection of

ammonite impressions Androgynoceras on the surface of a fallen

section of the Green Ammonite Member.

Right: A fragment of

ammonite shell Tragophylloceras from the Eype Clay

Member.

Left: A partial ammonite

Androgynoceras from the Green Ammonite

Member.

Right: Louis holds a

prized ammonite Androgynoceras found among fallen rocks

from the Green Ammonite Member.

Left: A small ammonite Androgynoceras from the Green Ammonite Member.

Right: An ammonite Liparoceras from the Green

Ammonite Member.

Left: A large

three-dimensional ammonite Liparoceras in situ Green

Ammonite Member. Right: An ammonite

Prodactylioceras.

Left: A tiny pyritised

ammonite and gastropod found among the foreshore pebbles.

Right: A pyritised ammonite Tragophylloceras.

Left: Visitors to

Seatown discover a nodule from the Green Ammonite Member, containing

ammonites Androgynoceras and ichthyosaur vertebrae.

Right: A close-up reveals three individual ichthyosaur vertebrae

towards the lower-left of the nodule, a rare and fantastic find for

these young fossil hunters.

Left: A small ammonite

Tropideroceras exposed in situ on the sea weathered

foreshore, Belemnite Marl Member.

Left: An ammonite

Amaltheus from the Eype Clay Member.

Right:

A small ammonite Protogrammoceras and a

brachiopod.

Right: An unidentified

ammonite exposed on the surface of a boulder originating from the

Thorncombe Sand Member.

Left: A collection of

belemnite guards from the Belemnite Marl Member, exposed on the sea

weathered foreshore. Right: A close-up.

Left: A belemnite guard from the Green

Ammonite Member. Right: A belemnite including the

phragmocone, undetermined horizon.

Left: The tip of a

belemnite guard exposed on a weathered foreshore boulder from the

Thorncombe Sand Member. Right: A second belemnite

example.

Left: A worn beach

pebble containing a partial vertebra and ribs belonging to an

ichthyosaur. Right: A fragment of bone, possibly a

large ichthyosaur rib.

Left: The tip of an ichthyosaur tooth found

among shingle. Right: A beach pebble

from the Belemnite Marl Member containing a small collection of crinoid

stems.

Left: A small displaced crinoid stem and partial

ammonite from the Eype Clay Member.

Right: A collection of

bivalve shells on the surface of a nodule from the Green Ammonite

Member.

Left: A large bivalve in situ within the Belemnite Marl

Member. Right: A bivalve from the Thorncombe Sand

Member.

Tools & equipment

It's a good idea to spend some time considering the tools and equipment you're likely to require while fossil hunting at Seatown. Preparation in advance will help ensure your visit is productive and safe. Below are some of the items you should consider carrying with you. You can purchase a selection of geological tools and equipment online from UKGE.

Hammer: A strong hammer will be required to split prospective rocks. The hammer should be as heavy as can be easily managed without causing strain to the user. For individuals with less physical strength and children (in particular) we recommend a head weight no more than 500g.

Chisel: A chisel is required in conjunction with a hammer for removing fossils from the rocks. In most instances a large chisel should be used for completing the bulk of the work, while a smaller, more precise chisel should be used for finer work. A chisel founded from cold steel is recommended as this metal is especially engineered for hard materials.

Safety glasses: While hammering rocks there's a risk of injury from rock splinters unless the necessary eye protection is worn. Safety glasses ensure any splinters are deflected away from the eyes. Eye protection should also be worn by spectators as splinters can travel several metres from their origin.

Strong bag: When considering the type of bag to use it's worth setting aside one that will only be used for fossil hunting, rocks are usually dusty or muddy and will make a mess of anything they come in contact with. The bag will also need to carry a range of accessories which need to be easily accessible. Among the features recommended include: brightly coloured, a strong holder construction, back support, strong straps, plenty of easily accessible pockets and a rain cover.

Walking boots: A good pair of walking boots will protect you from ankle sprains, provide more grip on slippery surfaces and keep you dry in wet conditions. During your fossil hunt you're likely to encounter a variety of terrains so footwear needs to be designed for a range of conditions.

For more information and examples of tools and equipment recommended for fossil hunting click here or shop online at UKGE.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING

FOSSILS

Protecting your finds

It's important to spend some time considering the best way to protect your finds onsite, in transit, on display and in storage. Prior to your visit, consider the equipment and accessories you're likely to need, as these will differ depending on the type of rock, terrain and prevailing weather conditions.

Left: Fossil

wrapped in foam, ready for transport. Right:

A small compartment box containing cotton wool is ideal for

separating delicate specimens.

When you discover a fossil, examine the surrounding matrix (rock) and consider how best to remove the specimen without breaking it; patience and consideration are key. The aim of extraction is to remove the specimen with some of the matrix attached, as this will provide added protection during transit and future handling; sometimes breaks are unavoidable, but with care you should be able to extract most specimens intact. In the event of breakage, carefully gather all the pieces together, as in most cases repairs can be made at a later time.

For more information about collecting fossils please refer to the following online guides: Fossil Hunting and Conserving Prehistoric Evidence.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Left: A birthday party with

a twist - fossil hunting at

Peacehaven.

Right: A family hold their prized ammonite at Beachy Head.

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it's your first time fossil hunting or you're looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more CLICK HERE