Established 2002

Lucinda Shepherd, friend Robert Randell and various experts for their support.

What is an echinoid?

Left: An internal flint mould of an echinoid (Echinocorys) from Peacehaven. Right: A small echinoid (Cidaris) from Woodeaton Quarry.

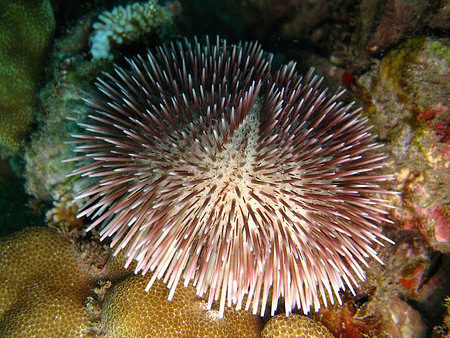

Despite their alien appearance, echinoids, or sea-urchins as they are better known, are very common in the seas and oceans of today and are common fossils too. Their name derives from the Greek 'echin' ('spiny'), referring to their protective spines and presumably 'ooid' (egg-like) in reference to their globular shell, or test as it is known. Echinoids are part of a much larger group of animals known as the Echinoderms ('spiny-skins'), which also includes the Asteroids (starfish), Holothurians (sea cucumbers), Crinoids (sea lilies and feather stars) and the Ophiuroids (brittle stars).

Though their body plans are varied, all echinoderms possess key features which unite the group:

-

A complex skeleton of calcareous plates, with a unique spongy structure known as stereom.

-

Five planes of symmetry, referred to as penta-radial.

-

An internal hydrostatic (water-vascular) system, external extensions of which are used for locomotion, respiration and feeding.

-

All live in marine waters.

From left: starfish, sea cucumber, crinoid, brittle star.

Echinoderms first appeared in the fossil record in the Cambrian around 530 million years ago and quickly diversified into many groups. Echinoids appeared in the Ordovician (around 450 million years ago (mya) but were not very successful at first and other groups such as crinoids dominated the Palaeozoic. By the beginning of Mesozoic (250 mya) many of the earlier echinoderm groups were extinct or in decline and the Echinoids rose to abundance. They diversified through the Jurassic (210-145 mya) and have remained successful ever since.

Why are Echinoids important?

Echinoids are very useful to palaeontologists because of their functional morphology; basically this means that by studying their anatomy you can tell a great deal about their mode of life and the environment in which they lived. They are also very common, and their robust tests and spines are easily fossilised and collected. Anyone who has hunted for fossils in the Jurassic and Cretaceous rocks of the UK will no doubt be very familiar with echinoids.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING FOSSILS

Regular or Irregular?

Echinoids fall into two categories; regular and irregular. This isn't referring to how common they are, rather to what shape they are. Regular echinoids have no front or back end and can move in any direction. Irregular echinoids have a definite front and back and do move in a particular direction. This is because regulars and irregulars have very different ways of life. Irregulars evolved from regulars, and their anatomy is therefore a modified version of the regular anatomy. For this reason we will deal with regulars first.

Regular Echinoids

As mentioned above, regular echinoids have no front or back end. Instead, the opening for the mouth (peristome) is on their underside, and the opening for the anus (periproct) is on top. When viewed from above or below their profile is circular and radially symmetrical; hence the term regular ('repeating', 'uniform'). This is because regular echinoids roam the surface of the sea floor in search of food and need to be able to move in any direction. This mode of life leaves them very exposed to predators and they have evolved elaborate spines both for defence and to act as stilts for locomotion.

Left: A living

echinoid feeding on the algae growing on a coral. Right:

Fossil echinoid (Phymosoma).

Most echinoids quickly loose their spines after death, and most fossil echinoids either comprise of isolated tests or solitary spines. However, if you are very lucky you may find a fossil echinoid which has been buried alive and still has its spines attached.

A typical regular echinoid spine (Phalacrocidaris

merceyi).

Spines vary greatly between species; some are needle-like, others club-like, some are poisonous and others possess thorny barbs. It is often easier to identify a species by its spines as opposed to its test, as they are much more variable and distinctive. Stripped of spines, many regular echinoids are superficially very similar.

Left: A living

echinoid with long spines. Right: A fossil regular

echinoid with club shaped spines (Pseudocidaris).

Once a regular echinoid finds food it can grasp it with its tube feet. These are tiny, fleshy suckers which extend from the hydrostatic water-vascular system through holes in the test. The holes through which they extend are organised into five distinct bands, called ambulacra, which run vertically between the peristome and the periproct. Regular echinoids are largely scavengers and have a varied diet of plant matter, animal detritus, sponges, molluscs and barnacles.

Left: Living

regular echinoid with light-purple spines and dark-pink tube feet.

Right: Living regular echinoid with its tube feet

extended.

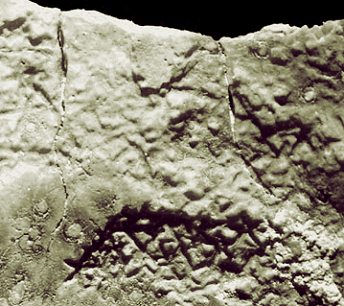

Regular echinoids possess large, powerful, and highly complex jaws, known as Aristotle's Lanterns, which extend through the mouth to collect food or scrape organics from shells or other hard surfaces. The jaws are complex beaks with five teeth. These leave a distinctive star-shaped grazing trace called Gnathichnus pentax. Isolated echinoid jaw-parts are not uncommon fossils, but because they are unfamiliar to most collectors they are either overlooked of misidentified.

Left: A fossil

regular echinoid which has broken open, revealing the impressive

beak-like jaws (Aristotle's Lantern) inside.

Right: Star-shaped incisions in a piece of oyster

shell caused by a regular echinoid scraping off organics.

Echinoids are armoured with minute defensive spines called pedicellariae. These are venomous or possess pincers to deter parasites and clear detritus. Pedicellariae are only preserved in exceptional circumstances.

High magnification picture of a

pedicellaria.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING

FOSSILS

Irregular echinoids

The first echinoids were regulars, and irregulars did not evolve until the Jurassic. Irregulars are much more common fossils though, and unlike regulars their tests are typically fossilised complete. Their spines are almost never found attached. Common forms are sea potatoes and sand dollars.

Left: Modern

irregular echinoid with small hair-like spines. Middle:

Fossil irregular echinoid. Right: A

modern sand dollar.

Irregulars lead a very different lifestyle from that of the regulars. They burrow along the sea floor and bulk-feed on the sediment to extract nutrients. For this reason the radial symmetry inherited from the regulars has been modified; the mouth moving to the front of the animal to collect food and the anus moving to the rear to leave waste behind. Hence their form is now irregular, with only one plane of symmetry.

The spines have lost their defensive role and have become reduced and hair-like. They now help to form the burrow, move the echinoid through the sediment, gather food and generate circulatory currents within the burrow. Many irregulars have lost their jaws as they are unnecessary to their mode of life. The tube feet are modified into flanges for respiration and gathering food, and the ambulacra are often sunken to form a petal shape on top of the echinoid.

Left: An irregular

echinoid (Echinocorys). Middle: Echinoid

(Nucleolites?). Right: Echinoid

(Clypeus).

Join us on a fossil hunt

Left: A birthday party with

a twist - fossil hunting at

Peacehaven.

Right: A family hold their prized ammonite at Beachy Head.

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it's your first time fossil hunting or you're looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more CLICK HERE