Established 2002

Lucinda Shepherd, friend Robert Randell and various experts for their support.

What is chalk?

Left: The famous Seven Sisters chalk cliffs in East Sussex. Right: A giant chalk ammonite exposed on the foreshore at Peacehaven.

Chalk is one of the best known of rocks, recognisable for its white colouration in striking land features such as the White Cliffs of Dover and Seven Sisters (pictured above), and familiar to most in everyday products such as blackboard chalk. Chalk has been exploited by man for thousands of years for both its physical and chemical properties and has fascinated scientists for centuries because of the fossils it contains and the geological story it tells.

How did the Chalk form?

Chalk is formed from lime mud, which accumulates on the sea floor in the right conditions. This is then transformed into rock by geological processes: as more sediment builds up on top, and as the sea floor subsides, the lime mud is subjected to heat and pressure which removes the water and compacts the sediment into rock. If chalk is subject to further heat and pressure it becomes marble.

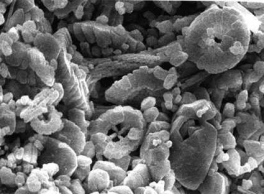

The lime mud is formed from the microscopic skeletons of plankton, which rain down on the sea floor from the sunlit waters above. The Coccolithophores are the most important group of chalk forming plankton. Each miniscule individual has a spherical skeleton called a cocosphere, formed from a number of calcareous discs called coccoliths. After death, most coccospheres and coccoliths collapse into their constituent parts.

Left: High

magnification image of chalk coccoliths. Right: An

individual coccolith.

Most chalks formed during the Cretaceous period, between 100 and 60 million years ago, and chalks of this age can be found around the world. The Cretaceous chalks record a period when global temperatures and sea levels were exceptionally high. This coincided with the break up of the supercontinent Pangea, which broke apart to form the continents of today. As continents move apart, an ocean forms between them, and new ocean-floor is added along the line of spreading (known as the mid-ocean ridge) by magma which rises from below. As the continents moved apart in the Cretaceous, a very high volume of magma rose up to form the new ocean-floor in what is known as a superplume event. The mid-ocean ridges became swollen, and large volumes of magma spilled out elsewhere onto the ocean floor, displacing water onto the continents (causing sea-level to rise). The volcanic activity also produced greenhouse gases which raised temperatures, prevented ice from forming at the poles and hence kept sea levels high. Chalks formed in the sea-ways of the flooded Cretaceous continents.

Why is chalk white?

Chalk is white because it is formed from the colourless skeletons of marine plankton. The same is true of many limestones, so why aren't they all white? The reason is that most limestones contain impurities, such as clays sourced from the land, or organics, which give them colouration. The Cretaceous chalk is free from impurities because sea levels were very high, so there was little land exposed to supply other sediments, and as the continental margins were flooded most land was far away. The Cretaceous sea floor was also very active so any organics were quickly broken down. The result was a very pure lime mud, formed almost entirely of planktonic skeletons.

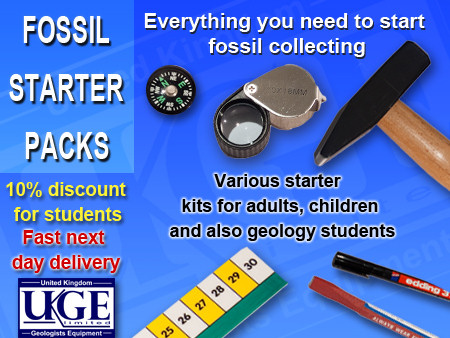

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING FOSSILS

Where can you find chalk?

Chalk cliffs are a familiar feature of the South and East coasts of England, and chalk downland runs between Devon and Yorkshire and across the counties of the South East. The Chalk also extends underground beneath London, the North Sea and the Channel. In England the Chalk Group is divided into three formations: the Upper Chalk, Middle Chalk, and the Lower Chalk.

The chalk was originally horizontal, but has been folded along with the other strata of southern England by continental movements over the last 30 million years. Throughout this period Africa has been pushing into Europe and creating the Alps. Britain is far from the site of impact, so the deformation is expressed more subtly by large, gentle folds, slowly uplifted and quickly eroded. The North and South Downs represent opposing sides of a great dome-like fold, whose roof has been eroded away to expose the older rocks of the Weald within. A quick rise in sea level after the last ice age flooded the broad valleys south and east of Britain, creating the North Sea and Channel, and incising into the downland to create the chalk cliffs of today.

What fossils might you find?

Fossils found in the Chalk Group record life on the Cretaceous sea floor. The chalk is very thick and deposition spanned 35 million years. The fossils found at the base of the Chalk Group (the oldest) differ from those at the top (the youngest) because of the many evolutionary and environmental changes that took place.

Chalk is composed of planktonic skeletons and is therefore made of micro-fossils. In fact, the coccolithophores that comprise chalk are small even by planktonic standards and are therefore termed nanno-fossils.

Chalk is an excellent material for fossil collecting and palaeontological studies. The rock is hard enough to preserve fossils in their original three dimensions, but soft enough to allow palaeontologists and collectors to carefully expose specimens from within the matrix. Among the most commonly found fossils within the chalk are bi-valves, echinoids, ammonites, bryozoans and sponges. Provided with access to a reasonable sized chalk exposure, a good picture of the range and volume of former life can be built in just a few hours of searching. Typically, only small-medium sized durable fossils are found, comprised of a single skeletal part (e.g. brachiopod shell, echinoid spine). Soft parts are never preserved.

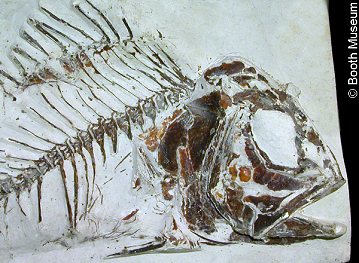

Occasionally chalk sediment was transported downslope and buried the inhabitants of the sea floor alive. Rare but spectacular fossils of exceptionally preserved fish, starfish, echinoids, crinoids and crustaceans record these events. Other scarce fossils include pterosaurs, ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and turtles. Very, very rarely, the remains of dinosaurs were carried out to sea.

Left: Chalk fish

(Hoplopteryx lewesiensis). Right: Chalk

starfish

(Metopaster parkinsoni).

A vast amount of chalk was quarried in England in the 19th Century, typically by hand. This was the heyday for chalk fossil collecting, as the blossoming of scientific study coincided with the industrial revolution and the demand for chalk. It was fashionable for gentleman scholars of the Victorian era to establish large fossil collections, and quarrymen were rewarded for any significant finds. Most important museum collections were established during this era.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING

FOSSILS

What can Chalk be used for?

Chalk has a great many uses to mankind, some familiar, some surprising. Many of you will use chalk all the time, either for chalking-up pool cues, drawing on blackboards or creating artwork. Sports-people such as gymnasts, athletes and mountain climbers use chalk on their hands and feet to provide grip.

Various uses of Chalk (from left):

drawing, writing on blackboards, snooker cue, athletics.

Chalk has been used as a building stone, and chalk rubble is often used in road construction. When heated chalk becomes lime, which has a great many applications. Lime is used in the production of Steel, Aluminium, Glass, paper, sugar, cement and fertilizer.

Various commercial uses of chalk

(from left): construction and building stones, lime for steel

production and agriculture.

The chalk strata itself is widely used as an aquifer, its network of fractures making it highly permeable. Abandoned chalk quarries are being developed as retail centres.

Chalk landmarks besides the famous White Cliffs of Dover, a great number of natural and man-made landmarks are found on the chalk coast and downland.

From left: Seven Sisters, East Sussex; Beachy

Head, East Sussex; Old Harry Rocks, Dorset and The Needles on the Isle of

Wight.

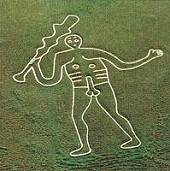

From left: Wesbury Horse, Wiltshire;

Uffington Horse, Oxfordshire; Long Man of Wilminton, E.Sussex and the Cern

Giant in Dorset.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Left: A birthday party with

a twist - fossil hunting at

Peacehaven.

Right: A family hold their prized ammonite at Beachy Head.

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it's your first time fossil hunting or you're looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more CLICK HERE