Introduction

Folkestone is a large coastal town in Kent, located a short distance west of the famous white cliffs of Dover, and is home to over 53,000 people. The town is fringed by rocky and sandy beaches, east and west of the harbour respectively. Fossils can be collected from the rocky beach and cliff base throughout the year. Access is good, although families with young children may find the terrain challenging.

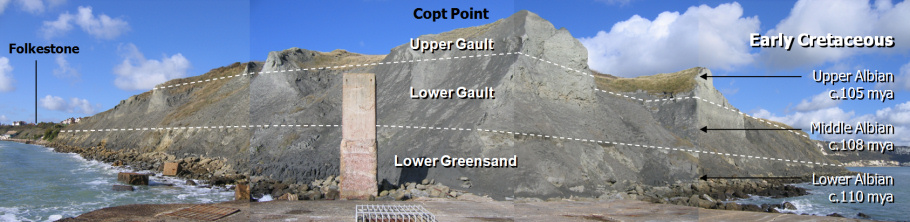

The earliest rocks at Folkestone date from the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous epoch, approximately 110 million years ago (mya), and were deposited within a shallow marine environment. These sandy rocks, known as the Lower Greensand, are eroded from the fragile cliffs east or the town, where they form a rocky beach extending for 1km around the headland at Copt Point. Overlying the Lower Greensand is the dark-grey coloured Gault clay, and it’s from this later (younger) marine sediment that Folkestone earns its reputation for fossils.

Parking is available along The Stade – a narrow road running along the top of the harbour. Food and refreshments are also available, including several good pubs and mobile restaurants.

Access to Copt Point (and beyond) is made along the arched promenade which extends from the harbour to the eroding cliff face (see above). The photo also shows the famous Martello Tower (painted white on the hilltop). The tower is one of many similar structures built in the early nineteenth century to defend the country from invasion by the French at that time.

The geology of Folkestone

The cliffs and foreshore east of Folkestone harbour reveal a fascinating prehistoric past dating from 110-105 mya (Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous epoch). During this time a warm sea, rich in flora and fauna, extended across South and South East England; Great Britain itself was located at a more southerly latitude (40°N), approximately where the Mediterranean Sea is today.

The rock succession at Folkestone records the ‘middle’ Cretaceous flooding of southern Britain (marine transgression). During the Early Cretaceous, Britain was a floodplain environment (above sea level). During the ‘middle’ Cretaceous, sea levels rose globally. Southern Britain was flooded from the southeast, receiving progressively less land-sourced sediment as sea-levels rose and the land disappeared. The Lower Greensand, which appears in the lower half of the cliff towards Copt Point and on the foreshore beyond (see figure 1 below), represents the initial marine stages during the Early Albian, when the land was still present and erosion of this land supplied the sands.

Sand is naturally derived from areas of high erosion, usually in relatively close proximity to a beach or within a river. Unlike finer particles of silt which may remain suspended within the water column and travel a greater distance, sand settles to the seafloor relatively quickly and is only transported further by strong tidal currents. The sandy composition and distribution of the Lower Greensand across the region reveals a moving shoreline (due to the marine transgression described above).

The Lower Greensand contains few delicate fossils, the most common fossils are large, thick-shelled molluscs, robust enough to withstand the strong currents and disturbed waters associated with a near-shore environment.

Resting conformably above the Lower Greensand at Folkestone is the Gault clay, a finer sediment transported further from land as sea levels continued to rise at the beginning of the Middle Albian c.108 mya. Only fine silts could be carried this far from land. The abundance of delicate, thin-shelled benthonic fauna (creatures living of the seafloor) is further evidence of relatively calm, undisturbed conditions. The Gault is divided into Lower (earlier) and Upper (later) sub-stages, and represents the greater proportion of the cliff face, see figure 1 above.

Continued flooding removed the land altogether in the Late Cretaceous, such that the only material left accumulating on the sea floor was the skeletons of marine plankton – resulting in the formation of the Chalk, exposed in the cliffs east of Copt Point (see figure 1 above, far-right).

Where to look for fossils?

The cliffs and foreshore east of the town are subjected to intense and sustained erosion from a number of forces, in particular the sea which breaks apart the fragile sandstone and clay (read more). This continuous process reveals fossils in situ and among the foreshore boulders on a daily basis, especially following periods or stormy weather.

Fossils can be found throughout the Lower Greensand and Gault, although the latter yields a far greater variety and volume of finds, and is the subject for the remainder of this investigation.

There are three areas where fossils from the Gault can be found: at the base of the slumping cliff, loose among the boulders, and at certain times (following scouring conditions) in situ within the exposed clay on the foreshore east of Copt Point.

Please note that this location is designated SSSI status, which requires visitors avoid digging directly into the cliff and foreshore; fossils can be found exposed in situ as shown above.

The base of the cliff (shown) is the best place to find Gault fossils, here the overlying clay has slumped over the underlying Lower Greensand, burying the latter from sight. Ammonite shells, bivalves and a range of other marine fossils can be found protruding from the surface, and are easily collected by hand. The quality of the fossils, especially the finer details, are best preserved if the specimen is collected directly from the clay.

Fossils can also be found loose among the boulders on the foreshore. At high-tide and during stormy conditions in particular, the soft clay is washed away, leaving the harder, more resistant fossils behind. These fossils (mainly fragments of ammonites and benthonic fauna) accumulate among the small spaces between the boulders.

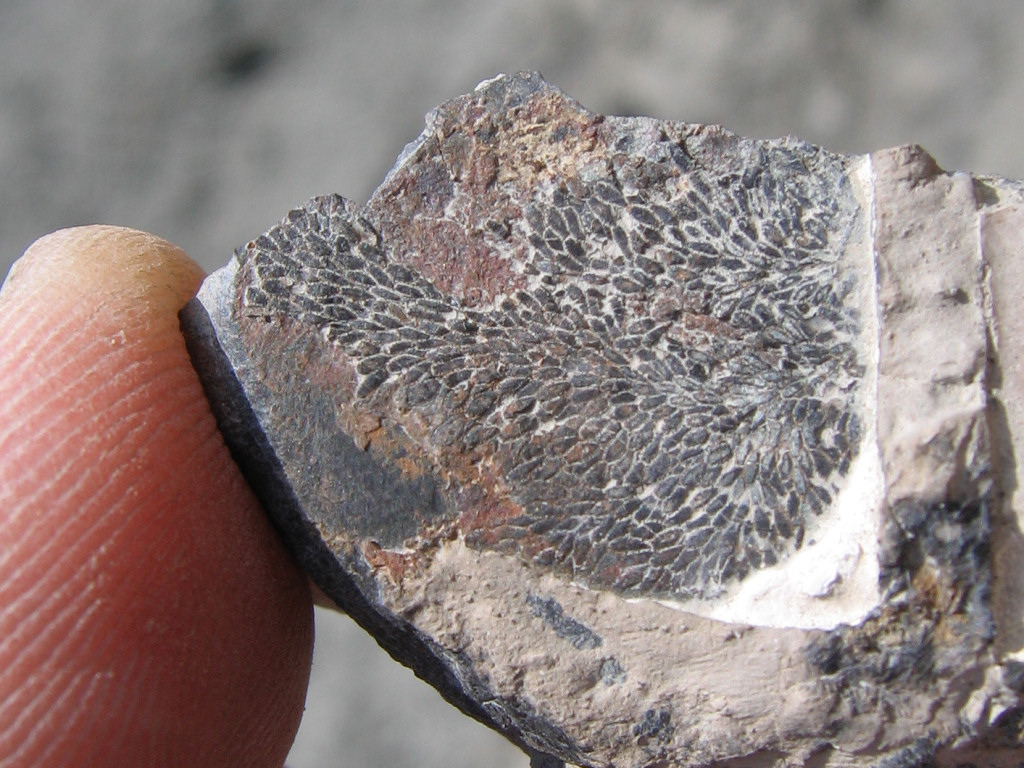

The photo above shows participants on a Discovering Fossils event searching for fossils among the boulders. Despite being exposed to the damaging forces of the sea, many of the loose fossils are surprisingly intact; however many are also broken into smaller fragments. The second photo above shows a beautiful fragment of ammonite shell, the suture marks (see ammonites) are clearly visible on the outer surface.

As with all coastal locations, a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

What fossils might you find?

The fossils within the Gault clay at Folkestone reveal a complex marine ecosystem, rich in life, in particular bivalves and cephalopods (ammonites and belemnites). The ammonites occur in a variety of shapes and sizes, including several species with uncoiled shells. Other common fossils include bivalves, gastropods, shark and fish teeth/bones, crab carapaces, goose barnacles and bryozoans.

Below are a selection of common finds made over several visits to Folkestone. The volume of fossils is usually sufficient that most visitors will find several complete or partial ammonites, belemnites and bivalves; fish, shark and crab remains are still common, but to a lesser extent.

References: A Geologic Time Scale, F. Gradstein, 2004; Folkestone population reference from www.wikipedia.org; Martello Tower history, www.martello-towers.co.uk; Fossil Fishes of Great Britain, Geological Conservation Review Series, D. L. Dineley and S. J. Metcalf; British Regional Geology, The Wealden District 4th edition, R. W. Gallois; A Dynamic Stratigraphy of the British Isles, R. Anderton and co; Ammonites and other Cephalopods, F. Clouter; various species identification www.gaultammonite.co.uk.