Established 2002

Lucinda Shepherd, friend Robert Randell and various experts for their support.

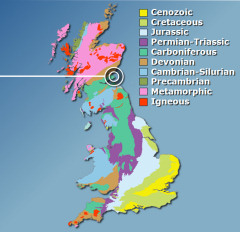

Crail (Fife)

Click above to view page as a PDF.

Click here to download PDF software.

Introduction

Crail is a small fishing village located in south east Fife (Scotland) and provides a fascinating insight into the Carboniferous period 335 million years ago. What distinguishes Crail from the surrounding localities is the occurrence of several well preserved Arthropleura (giant centipede) trackways, which can be seen in situ in the neighbouring bay. Please note, the trackways are scientifically important and must not be collected or damaged, we ask that all visitors respect this.

Left: View over

Crail harbour from the road leading into the village.

Right: A small coffee shop provides refreshments and views

over the bay.

Parking is available throughout the village and a small coffee shop provides refreshments and stunning views across the bay. Access to the beach is made alongside the western edge of the harbour (see photo above-left), this leads into the first of several small bays described below.

The geology of Crail

The rocks at Crail were formed within an expansive delta system during the Carboniferous period (Visean stage / Holkerian sub-stage), approximately 335 million years ago. Much of the rock exposed today was formed by sands and silts carried and deposited by rivers across the region. It's interesting to note that at this time the river system flowed south west, completely opposite to the present situation; the source of the rivers during this time was where the North Sea is today.

This period represents a great change in the earth's history, with land plants evolving into large trees and ferns, and amphibians, reptiles and giant flying insects inhabiting the humid forests. One of the notable inhabitants of the forest floor was Arthropleura, a giant centipede which evolved from crustacean-like ancestors and was able to grow larger than modern Arthopods because of the high percentage of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere at that time and because of the lack of large terrestrial predators.

Where to look for fossils?

Fossils can be found among the pebbles and foreshore exposures within each of the neighbouring bays west of the harbour. Heading along the beach (at low tide) the first fossil you're likely to encounter is a giant tree stump (see below-left); continuing further you'll shortly reach the site of the Arthropleura tracks (see below-right).

Left: Giant tree

stump visible in the bottom-left of the photo. Right:

Horizontal bedding and location of the Arthropleura tracks.

There are several Arthropleura tracks, the most striking of which is located above sea level in the cliff section shown above-right. The first bay ends shortly after the tracks, beyond which several more bays can be found and provide the best opportunity to collect fossils.

As with all coastal locations, a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download a free trial click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

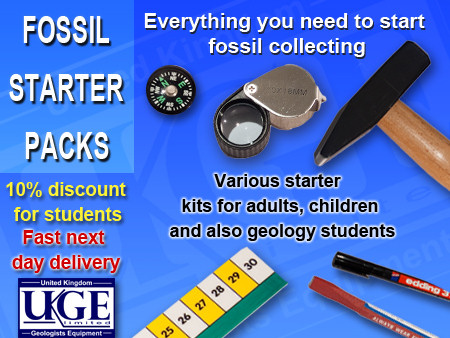

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING FOSSILS

What fossils might you find?

Crail is most famous for the occurrence of Arthropleura trackways in the cliffs and on the foreshore boulders; these impressive giant centipedes measured up to 2 meters (over 6 feet) in length and comprised of an armoured exoskeleton and dozens of sharply pointed legs running along its underside.

A model Arthropleura

displayed in the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow.

The spacing of the tracks at Crail indicate this particular specimen measured over 4 feet. The most impressive pair of tracks occur above the foreshore (described above), each comprising two clear uniform impressions of the creatures many feet. Given the similarity of the two tracks and the unique circumstances that led to their preservation, it's most probable that they were left by the same creature within a short time of each other (possibly the same day).

Left: A trace fossil -

two trackways left

in the sediment by an

Arthropleura giant 'centipede'

hi-res image. Right: A close-up of the tracks.

Important: Please respect the trackways and do not damage or attempt to collect any part of them. We wish to remind visitors that these are extremely rare and scientifically important (in their life position).

During our recent visit we observed a further two separate trackways, as shown below; these particular specimens are being subjected to extensive weathering by the sea, the result of which is apparent and a great shame. We hope that the addition of Crail to the website may serve to amplify the efforts to preserve them.

Left: A second

Arthropleura trackway on a foreshore boulder.

Right: A third trackway.

As well as several trackways the first bay is also host to a range of other fossils, in particular a large tree stump (below-right) and ripple marks formed in the Carboniferous sediment (below-left).

Left: Ripple marks

on the surface of a large foreshore boulder. Right:

A large tree stump on the foreshore.

Hammering is not recommended in this area, as the vast majority of finds are in situ and should be left for others to observe. Among the foreshore boulders it's possible to collect small pebbles containing evidence of trees and other vegetation present at the time; the specimens below show two separate types of tree material.

Left: A fragment of

tree bark (Lepidodendron). Right: Another

fragment of tree bark.

The most common fossils along this stretch of coast are the trunk and roots of Lepidodendron trees, which appear in situ of the foreshore. The bark is identifiable by its characteristic diamond-shaped leaf cushions, whereas the roots (known commonly as Stigmaria) are covered by a series of small pits (see below-left), from which smaller root appendages grew. Some Lepidodendron species could grow up to 40 metres; the roots spread horizontally, indicating humid environments.

Left: Stigmaria

(Lepidodendron root). Right: A

large section of unidentified tree trunk.

Left:

Stigmaria (Lepidodendron root). Right:

Stigmaria impression (Lepidodendron root).

Leaving the first bay and moving further along the foreshore, the volume of beach pebbles increases and as does the opportunity to collect fossils. If you're equipped with a hammer and chisel (see equipment) you can find a variety of fossils within them. The photo below-right shows a closeup of a split pebble, within which a small bivalve shell can be seen alongside plant debris. The presence of these two fossils indicates the environment was densely vegetated and in immediate proximity to water.

Left: A split beach

pebble containing plant and shell remains. Right:

A close-up of the bivalve and vegetation.

Left: Section

of unidentified tree bark (Lepidodendron?). Right:

Section of tree trunk (Lepidodendron).

Please note, the foreshore west of Crail is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), which makes it illegal to hammer or remove any situ material.

Tools & equipment

It's a good idea to spend some time considering the tools and equipment you're likely to require while fossil hunting at Crail. Preparation in advance will help ensure your visit is productive and safe. Below are some of the items you should consider carrying with you. You can purchase a selection of geological tools and equipment online from UKGE.

Hammer: A strong hammer will be required to split prospective rocks. The hammer should be as heavy as can be easily managed without causing strain to the user. For individuals with less physical strength and children (in particular) we recommend a head weight no more than 500g.

Chisel: A chisel is required in conjunction with a hammer for removing fossils from the rock. In most instances a large chisel should be used for completing the bulk of the work, while a smaller, more precise chisel should be used for finer work. A chisel founded from cold steel is recommended as this metal is especially engineered for hard materials.

Safety glasses: While hammering rocks there's a risk of injury from rock splinters unless the necessary eye protection is worn. Safety glasses ensure any splinters are deflected away from the eyes. Eye protection should also be worn by spectators as splinters can travel several metres from their origin.

Strong bag: When considering the type of bag to use it's worth setting aside one that will only be used for fossil hunting, rocks are usually dusty or muddy and will make a mess of anything they come in contact with. The bag will also need to carry a range of accessories which need to be easily accessible. Among the features recommended include: brightly coloured, a strong holder construction, back support, strong straps, plenty of easily accessible pockets and a rain cover.

Walking boots: A good pair of walking boots will protect you from ankle sprains, provide more grip on slippery surfaces and keep you dry in wet conditions. During your fossil hunt you're likely to encounter a variety of terrains so footwear needs to be designed for a range of conditions.

For more information and examples of tools and equipment recommended for fossil hunting click here or shop online at UKGE.

ADVERTISEMENT BY UKGE - OFFICIAL ADVERTISING PARTNER OF DISCOVERING

FOSSILS

Protecting your finds

It's important to spend some time considering the best way to protect your finds onsite, in transit, on display and in storage. Prior to your visit, consider the equipment and accessories you're likely to need, as these will differ depending on the type of rock, terrain and prevailing weather conditions.

Left: Fossil

wrapped in foam, ready for transport. Right:

A small compartment box containing cotton wool is ideal for

separating delicate specimens.

When you discover a fossil, examine the surrounding matrix (rock) and consider how best to remove the specimen without breaking it; patience and consideration are key. The aim of extraction is to remove the specimen with some of the matrix attached, as this will provide added protection during transit and future handling; sometimes breaks are unavoidable, but with care you should be able to extract most specimens intact. In the event of breakage, carefully gather all the pieces together, as in most cases repairs can be made at a later time.

For more information about collecting fossils please refer to the following online guides: Fossil Hunting and Conserving Prehistoric Evidence.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Left: A birthday party with

a twist - fossil hunting at

Peacehaven.

Right: A family hold their prized ammonite at Beachy Head.

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it's your first time fossil hunting or you're looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more CLICK HERE