Introduction

Charmouth was one of the first locations added to Discovering Fossils and has since been the destination for several organised fossil trips. The famous coastline between Lyme Regis (in the west), and Seatown (in the east), has yielded a range of spectacular fossils, including: giant marine reptiles, intricate crinoids and ammonites.

The beach and cliffs are part of the Jurassic Coast (World Heritage Site), which encompass 95 miles of coast between Dorset and Devon. The area is well suited to amateur and experienced fossil hunters alike – throughout the year visitors flock in their masses to scour the beach for fossils washed out of the cliffs and foreshore.

The rocks at Charmouth date predominantly from the early part of the Jurassic period (around 190 million years ago), during which time this area lay beneath a warm, shallow sea, closer to the equator, approximately where North Africa resides today.

Charmouth is well equipped for visiting fossil hunters – parking, refreshments and a visitor centre displaying local finds are available all year round, alongside the mouth of the river Char (see below). From the car park visitors can follow the beach in an easterly or westerly direction. The following page covers the journey east, beneath Stonebarrow Hill and towards Golden Cap and Seatown.

The geology of Charmouth

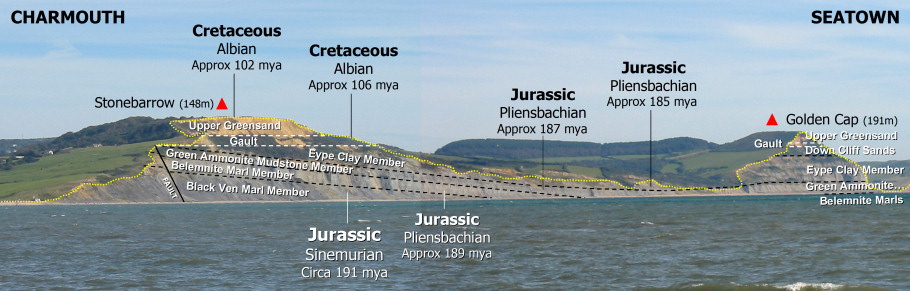

The cliffs and foreshore between Charmouth and Seatown represent two stages within the Early Jurassic (or Lias) period known as the Sinemurian and Pliensbachian, dating from approximately 190-185 million years ago. During this time, an enormous, generally shallow epicontinental sea (less than 100m deep), spread over this area of the world and laid down alternating layers of clay and limestone. At that time, Charmouth (as it’s now known) lay closer to the equator, roughly where North Africa is today. Overlying the Jurassic sediments are younger Cretaceous deposits, including the Gault and golden coloured Upper Greensand (green when freshly split) – deposited around 106-102 million years ago (see fig. 1 below).

See Lyme Regis for geology and fossils towards the west.

Fossils can be found throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous exposures between Charmouth and Golden Cap, however it’s the Jurassic rocks in particular that attract fossil hunters to Charmouth.

Life was abundant during the Jurassic period, giant marine reptiles inhabited the seas and pterosaurs flew across the skies. This was also the time of the dinosaurs, however the presence of sea over much of the area and distance from any significant landmass means their fossils are rarely found at Charmouth.

There are five important members present in the cliffs (not including the overlying Cretaceous sediments) between Stonebarrow and Golden Cap from which a variety of fossils can be collected:

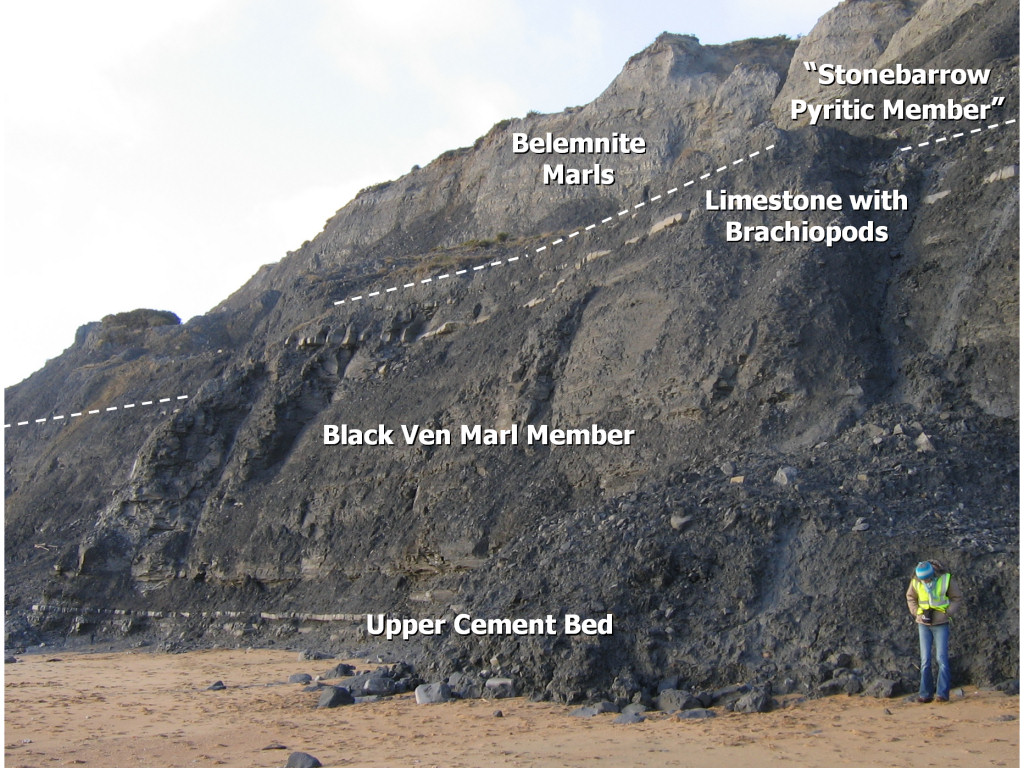

Black Ven Marl Member – This is the lowest and oldest of the sediments present beneath Stonebarrow and is the first to be encountered travelling east, towards Golden Cap. The name is taken from the cliffs west of Charmouth – Black Ven, where the complete member is exposed. The full thickness of the member comprises 44m of mostly dark-grey mudstones, with subordinate beds of nodular and tabular limestone. The most conspicuous marker within the Black Ven Marls is known as the Lower Cement Bed (see fig. 2 below). This 0.3m thick limestone bed is visible in the lower part of the cliff beneath Stonebarrow, before disappearing beneath the shingle about 1,500m from the beach access point. Overlying the Lower Cement Bed (5m higher) is the Upper Cement Bed.

The Upper Cement Bed (pictured at beach level, fig.3 above), is identifiable by two closely spaced limestone bands. The photo above also shows the overlying Limestone with Brachiopods Bed (11m higher). It’s recently been proposed to separate and name the upper 17m of the Black Ven Marl Member, the ‘Stonebarrow Pyritic Member’ (fig.4 and 6 below), although this is not yet formerly recognised and its inclusion within quotation marks is for illustrative purposes only.

Dr Paul Davis (NHM London): ‘There are high volumes of pyritic fossils throughout the Black Ven Marl Member, however there is a distinct lithology change and it may – on a sedimentological basis – be sensible to separate the two units. As an aside the upper ‘unit’ pyritic fossils are much more susceptible to pyrite decay than those from below (e.g. how many pyritic Promicroceras decay as opposed to pyritic Echioceras or Eoderoceras!) I also think that this boundary (which is marked by the top of the Coinstones – Bed 89 of Lang) is mapable inland. It also represents a major nonconformity where 6 ammonite subzones are missing as there was a long period of non deposition – this can be seen on the top of the Coinstones by the fact they were exposed on the seabed for a long period of time – it is bored and has a very eroded upper surface and can make an obvious ledge or break in slope when looking at the cliffs.’

The proposed base of the ‘Stonebarrow Pyritic Member’ is 3m above the prominent Limestone with Brachiopods Bed (fig. 4 and 5) and extends upwards to the overlying, pale coloured, Belemnite Marl Member. The total thickness of the member would be approximately 17m.

These dark-coloured sediments are largely responsible for the volume of pyrite ammonites that scatter the foreshore, including: Crucilobiceras, Eoderoceras, Echioceras and the distinctive (smooth surfaced) Oxynoticeras lymense.

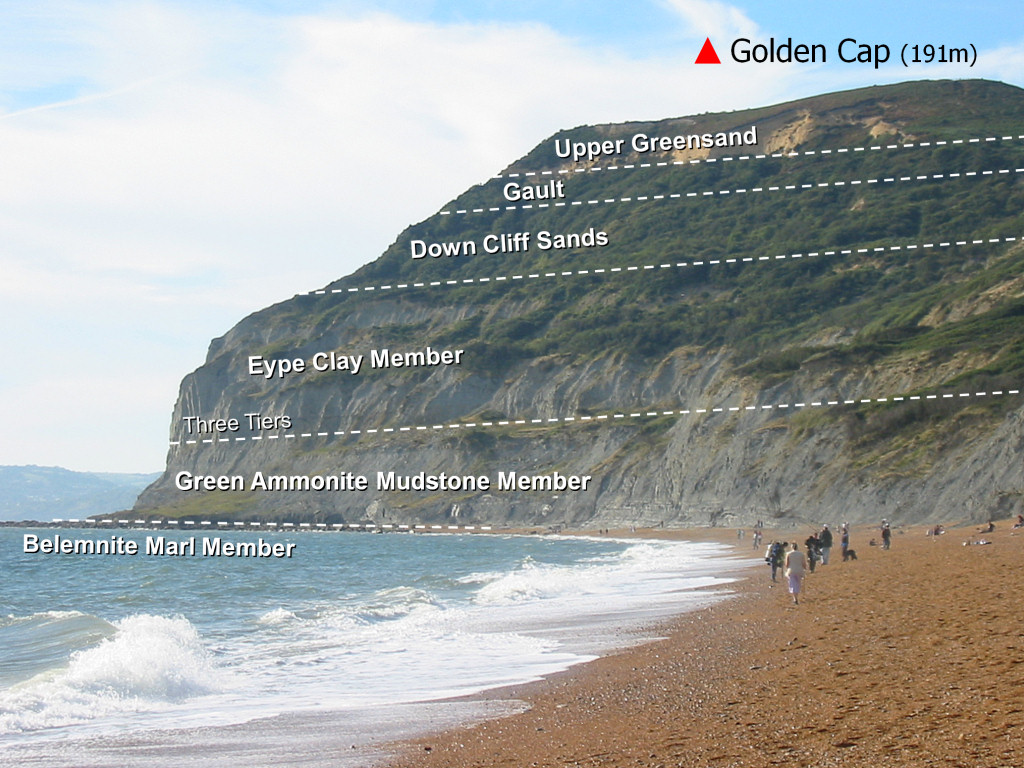

Belemnite Marl Member: These deposits are seen towards the top of the cliffs, but are best examined beneath the eastern side of Golden Cap, where they reappear on the sea-weathered foreshore. During a low-tide belemnite guards can be seen in abundance protruding from the exposed rock surface. Although abundant the in situ belemnites are protected by the SSSI status of the area and should not be removed manually. Fortunately a large number of belemnite guards can be found loose among the shingle and boulders. Despite the name given to the Belemnite Marl Member ammonites are also abundant throughout the sediments.

The Belemnite Marls are easily identified by their alternating pale and dark horizontal bands (fig. 6 and 7). The different shades of grey are the result of the differing organic carbon content (higher in the darker bands). The Belemnite Marls extend 23m upwards to the overlying Green Ammonite Mudstone Member.

Green Ammonite Mudstone Member: This member rests above the Belemnite Marls and measures some 15m thick at Stonebarrow and 34m at Golden Cap. Ammonites are abundant and include species of Aegoceras, Oistoceras, Liparoceras, Tragophylloceras and Androgynoceras (below).

Although present in the upper part of the cliffs at Stonebarrow the Green Ammonite Mudstone Member is best observed at the base of Golden Cap (fig. 8) and beyond, towards Seatown. Please take additional care and wear a hard hat if venturing anywhere near the cliff itself, rock falls occur on a daily basis.

Eype Clay Member: The base of the Eype Clay Member is marked by three well-cemented, fine-grained, mudstones, each 0.5-1m thick – indicating an abrupt end to the underlying Green Ammonite Mudstone Member. These mudstones (known as the Three Tiers) form prominent ledges in the cliff (fig. 9 and 10).

Above the Eype Clay Member lies the Down Cliff Sands (fig. 10), however material from this unit is less commonly found at beach level and is not the subject of this particular location review. Above this lies the younger Gault and Upper Greensand dating from the Cretaceous period.

Where to look for fossils?

Fossils can be found along the entire coastal stretch between Charmouth and Seatown, although the volume is highest within within the first 1,000m of the beach access point. The best and safest place to search is amongst the shingle and exposed foreshore at low-tide as shown below.

During a falling tide fossils are deposited between the high and low-water mark and are easily found with a keen eye. Among the most common finds include: pyritised ammonites, belemnite guards and crinoid stems. It’s also worth examining the clay accumulations at the base of the slumping cliffs (see below); however, this should only be attempted where there’s a minimal risk of injury from falling rocks. For much of the year it’s possible to examine the toe (end) of the clay accumulations without getting too close to the cliff itself. As always, a reasonable judgement must be applied at the time and children should be closely supervised.

The toe of the clay accumulations (‘Stonebarrow Pyritic Member’ in this instance) are often subject to weathering from the sea at high-tide and during stormy conditions in particular. This process washes away the soft clay exposing the more resistant fossils on the surface (see above). Using a small steel point (see equipment) it’s possible to gently ease exposed fossils from the clay.

Continuing along the beach (towards Seatown) you eventually reach the towering cliffs beneath Golden Cap. At this point the Green Ammonite Mudstone Member is exposed in the lower part of the cliff, within which some very well preserved ammonites in particular can be collected. For more information about the features and processes shaping coastal fossil collecting locations click here.

As with all coastal locations, a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

What fossils might you find?

Charmouth is a destination for thousands of fossil hunters each year, and for good reason, this is one of the best fossil collecting locations in the country. Ammonites, nautili, belemnites, crinoids, bivalves, fish, marine reptile bones and even insects, and occasional dinosaur bones, can all be found here. The most commonly collected fossils are pyritised ammonites – with a little patience and a keen eye most visitors will find at least one. To read more about ammonites click here.

Below are a selection of finds made over several visits. If you find something of particular interest during your own visit please seek advice and support at the Charmouth Heritage Centre – alongside the car park.

References: www.jurassiccoast.com; British Lower Jurassic Stratigraphy, M.J.Simms; R.Edmonds, Discover Dorset – Fossils; The Geology of Britain, P.Toghill; http://www.g6csy.net/fossil/bvm.html; A Dynamic Stratigraphy of the British Isles, A. Anderton and co; Dr Ian West, www.soton.ac.uk; A Geologic Time Scale 2004, by F. Gradstein, J. Ogg and A. Smith. Many thanks to Dr Neville Hollingworth for his ammonite identifications. Special thanks to Prof. Norman MacLeod and Dr Paul Davis at the Natural History Museum of London for their support and advice.