Introduction

Beachy Head is an area of spectacular coastline and countryside located on the most southerly tip of East Sussex, 1.5 miles southwest of Eastbourne. The area is well known for its chalk cliffs that tower above the characteristic Beachy Head lighthouse with its red and white striped paintwork. The cliffs between Eastbourne and Beachy Head are part of a sequence of cliffs that extend a further 4.5 miles to Cuckmere Haven in the northwest, and encompass the famous undulating contour of Seven Sisters.

Above: View west at Beachy Head during low-tide; the lighthouse is dwarfed by the towering chalk cliffs.

Above: View west at Beachy Head during low-tide; the lighthouse is dwarfed by the towering chalk cliffs.

The rocks and clays at Beachy Head span 17 million years of deposition between 103-86 million years ago (mya), and record the transition from shallow, near-shore conditions to deeper water and the earliest associated chalks. Fossils occur commonly throughout the chalk, in particular echinoids, sponges, bivalves, and other benthic fauna that inhabited the prehistoric seafloor at the time.

Above: Two children admire an ammonite Mantelliceras discovered on a loose boulder.

Above: A ‘Pecten’ bivalve

The best place to access Beachy Head is from Eastbourne, via King Edward’s Parade which runs along the seafront. At the western end of the seafront the road bends to the right and continues up the hill, at which point parking is available outside a small cafe.

Above: Parking is available at the end of the coast road.

From the parking area a public footpath runs alongside the cafe, past an iron gate (shown above) and towards the cliff-top. The path follows the coastline approximately 1.5 miles to Cow Gap, at which point a flight of metal steps extend to the beach.

Above: Following the hill-top along the coast, signposts direct the way to Cow Gap.

The geology of Beachy Head

The rocks and clays at Beachy Head record a fascinating history dating from the Late Cretaceous epoch, c.103 to c.86 mya, and provide evidence of dramatic geological changes that took place during this time. Among the events recorded is the transition from a shallow near-shore environment, during which sands and clays were deposited, to higher sea levels and the first associated grey and white chalks. At this time Beachy Head and much of Great Britain, along with Europe, lay around 40°N of the equator, on an equivalent latitude to the Mediterranean Sea today.

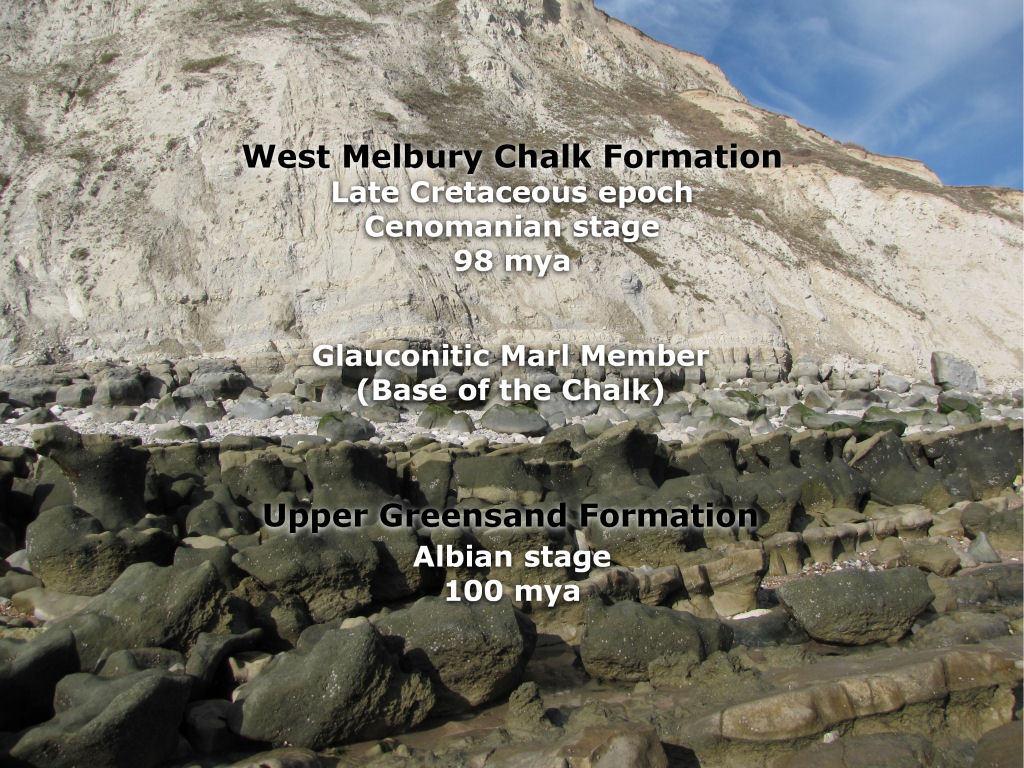

Figure 1: View from Cow Gap overlooking the earliest deposits exposed and the transition to the Chalk at the cliff base. *Limited in situ material, mostly boulders.

The earliest deposits at Beachy Head belong to the Upper Gault, a dark grey, sticky (when wet) clay dating from the Upper Albian stage, approximately 103 mya (see fig.1 above and photo below-left). The Gault clay is understood to have formed relatively close to land (compared to chalk), but at sufficient distance and depth that the seabed was undisturbed by wave energy and strong tidal currents, that might otherwise have introduced a greater volume of sand to the sediment. Only fine silts could be carried this far from land. The abundance of delicate, thin-shelled benthonic fauna (creatures living of the seafloor) is further evidence of relatively calm, undisturbed conditions.

Above: The Gault clay on the foreshore at Cow Gap is the earliest deposit at Beachy Head.

Above: The overlying Upper Greensand visible in situ in the foreground.

Above: The overlying Upper Greensand visible in situ in the foreground.

Resting above the Gault clay but below the overlying Chalk is the Upper Greensand (above-right), a course sandy sediment which probably reflects a minor regressive phase, during which the lower sea level reduced the distance from land and allowed sand to be reintroduced to the area.

Overlying the Upper Greensand is the Chalk including the Glauconitic Marls at its base. Figure 2 below-left shows the transition from Upper Greensand (visible on the foreshore) to the overlying Chalk (visible in the cliff). As sea levels rose, pushing the coastline further away, the volume of land sourced sediment that contributed to the Upper Greensand gradually reduced, leaving one main source for continued sedimentation – marine plankton.

Figure 2: Transition from Upper Greensand to the overlying Chalk as sea levels rose.

Above: The chalk cliffs tower above the foreshore towards the lighthouse.

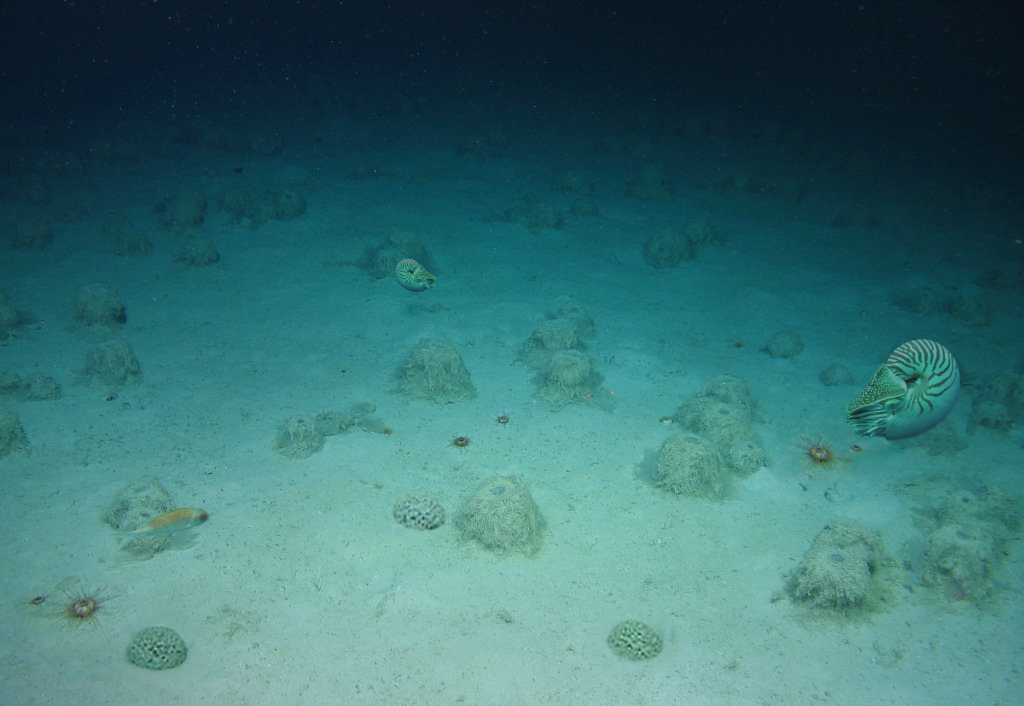

The Chalk is largely comprised of the skeletal remains of planktonic algae known as coccolithophores which accumulated to form a white ooze on the seafloor. This soft sediment was later compacted and hardened (lithified) to form chalk – a relatively soft rock itself. The evidence of higher sea levels is reflected in the progressively white chalk seen higher in the cliffs. The purity of the chalk indicates its formation took place far from land, free of terrestrial sands and silts that would otherwise have coloured it.

Above: A reconstruction of how the Chalk seafloor might have appeared during its formation. © Roy Shepherd and Robert Randell.

Above: A reconstruction of how the Chalk seafloor might have appeared during its formation. © Roy Shepherd and Robert Randell.

In comparison with present-day conditions, global sea-levels during the Late Cretaceous were over 200 meters higher. The higher sea levels likely reflect a combination of extreme greenhouse conditions and heightened plate tectonics. Elevated plate tectonic activity and the associated volcanics delivered greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, fuelling the greenhouse effect. Global high temperatures melted much (perhaps all) of the ice at high latitudes, introducing significant amounts of water to the world’s oceans. Uplift of the ocean-floor in regions of active plate tectonics displaced further water onto the continental shelves.

Today the chalk appears above sea level, the result of lower present-day sea levels and widespread uplifting caused by the pressure of the European and African continental plates colliding (generating the Alps), a process that took place at its greatest extent 30-25 mya. More recently, following the end of the last ice age and subsequent increase in sea levels (albeit to a less extent than 84 million years ago), the coastline has moved inland, exposing the elevated chalk to intensive erosion and sculpting it into a vertical cliff-face.

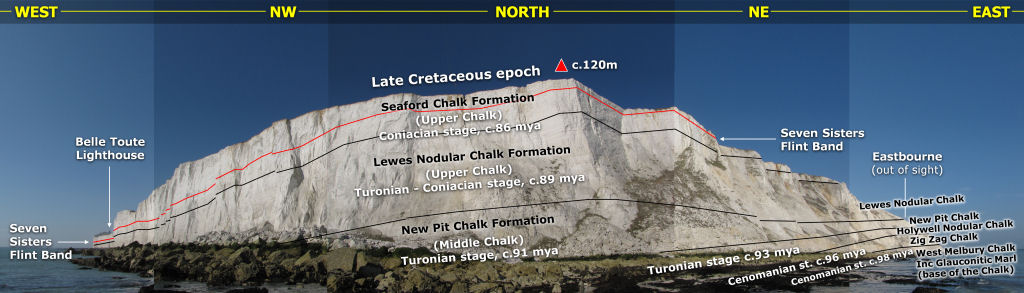

Figure 3 and 4 below provide a summary of the geological horizons present in the cliffs and on the foreshore east of Cow Gap. The first is taken from the end of Head Ledge looking back towards the cliffs and lighthouse, and the second is taken from the base of the lighthouse. Beachy Head is one of only a small number of UK locations where the Lower, Middle and Upper Chalk is exposed.

Figure 3: Summary of the key geological horizons visible from Head Ledge towards Beachy Head lighthouse to the west and Eastbourne to the northeast.

Figure 4: Summary of the key geological horizons seen from Beachy Head lighthouse towards the Belle Tout lighthouse in the west and Head Ledge in the east.

One of the key markers visible in the cliff-face is the Seven Sisters Flint Band, a conspicuous dark-coloured sheet flint visible within the Seaford Chalk at the cliff-top opposite Beachy Head lighthouse (indicated as a red line in figures 3 and 4 above). Travelling west, beyond the Belle Tout lighthouse, the Seven Sisters Flint Band reaches beach level (shown below-left).

Above: Seven Sisters Flint Band at beach level, west of Beachy Head.

Above: Seven Sisters Flint Band (SSFB) high in the cliffs opposite Beachy Head lighthouse.

Above: Seven Sisters Flint Band (SSFB) high in the cliffs opposite Beachy Head lighthouse.

Although flint is inorganic, the silica that formed it was originally sourced from the remains of sea sponges and siliceous planktonic micro-organisms (diatoms, radiolarians). Flints are concretions that grew within the sediment after its deposition by the precipitation of silica; filling burrows/cavities and enveloping the remains of marine creatures, before dehydrating and hardening into the microscopic quartz crystals which constitute flint. To discover more about flint click here.

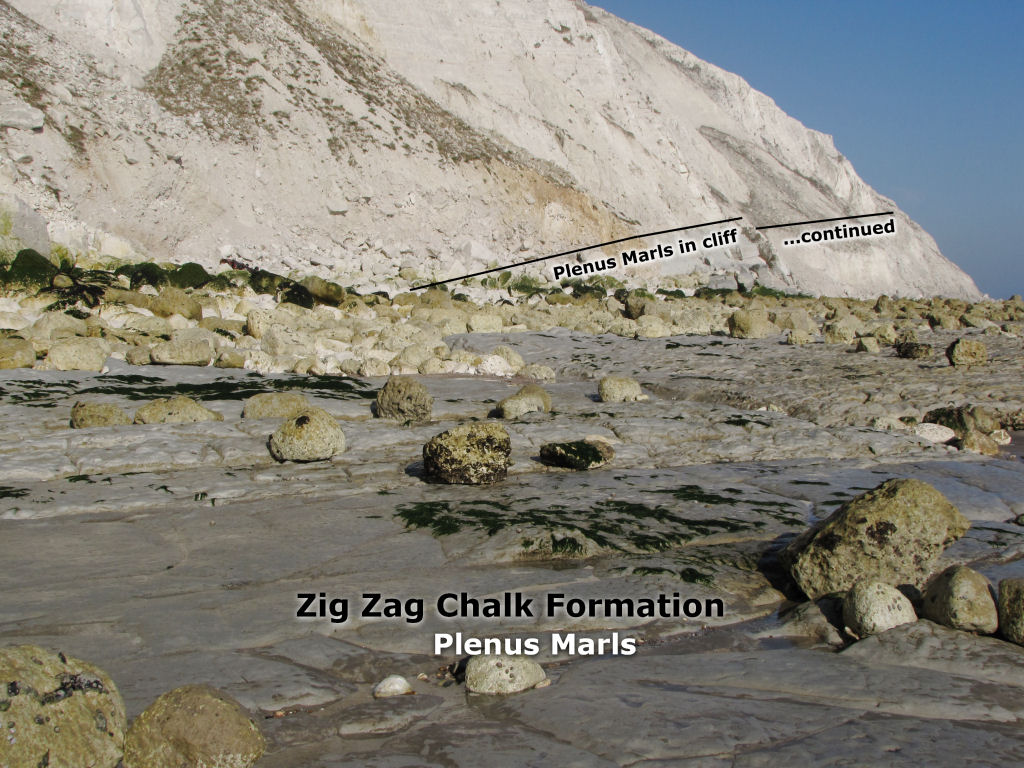

Another point of interest are the Plenus Marls, a band of darker-grey chalk (c.8m thick) located in the uppermost portion of the Zig Zag Chalk Formation. From Hedge Ledge the gradual dip of the chalk brings the Plenus Marls to beach level a short distance east of the lighthouse (fig.5 below-left).

Figure 5: Plenus Marls (named after the belemnite Actinoclamax plenus found within them) exposed on the foreshore and in the cliff east of the lighthouse.

Above: A belemnite guard Actinoclamax in situ within the Plenus Marls.

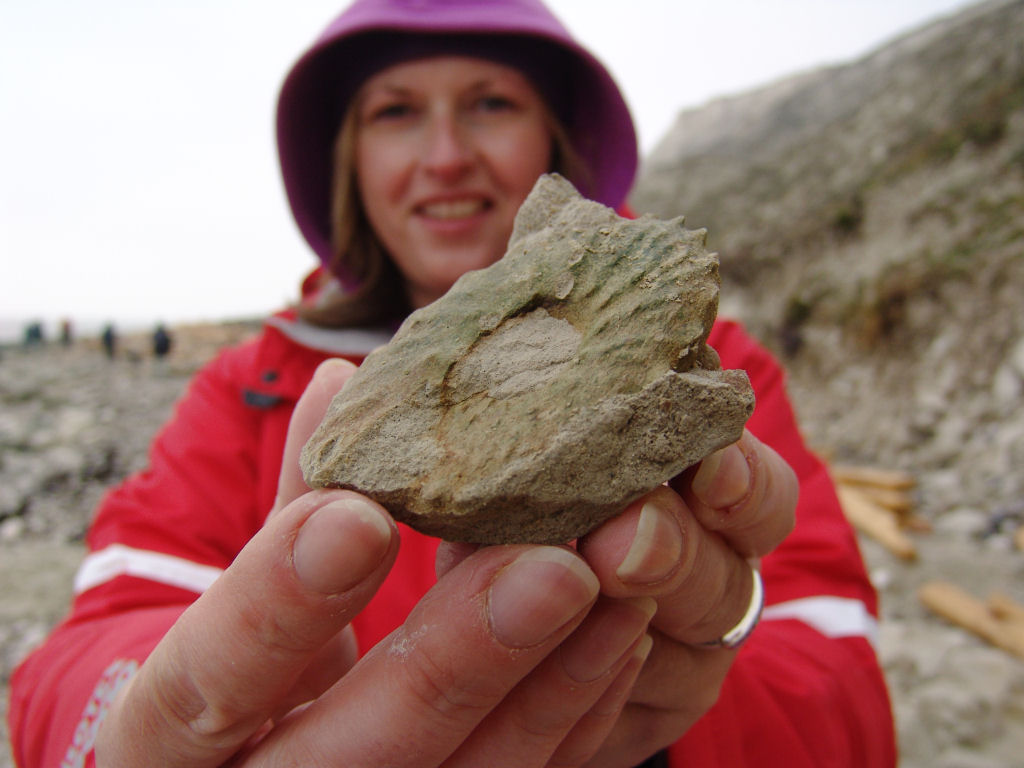

At low-tide the Plenus Marls are well exposed on the foreshore, providing an opportunity to search for the comparatively rare belemnite guards belonging to Actinoclamax (above-right). The guards can sometimes be found exposed on the surface of the eroding beach platform; their dark-amber colouration and semi-translucent character makes them easily distinguishable from the surrounding chalk matrix.

Where to look for fossils?

Fossils can be found on the foreshore and at the base of the cliffs in either direction from Cow Gap. The most productive (and safest) place to search for fossils is on the foreshore at low-tide. Chalk boulders and flint nodules are scattered along the entire section, providing a constant supply of fossils.

Above: Lucinda searches for fossils among the flint pebbles on the foreshore.

Above: Lucinda searches for fossils among the flint pebbles on the foreshore.

Above: Robert shows an event participant an ammonite within a loose boulder.

For first time visitors and families in particular, the stretch of low-gradient cliff immediately southwest of the steps at Cow Gap provides a relatively safe and productive location to search for fossils. The chalk here belongs to the West Melbury Marly Chalk Formation and is rich in ammonites and bivalves in particular (below-left).

Above: Loose rocks at the base of the low-gradient cliff (West Melbury Marly Chalk).

Above: A split chalk rock containing an Mantelliceras ammonite.

Please note the beach platform and cliffs are assigned SSSI status, which requires visitors avoid damaging (including hammering) the area. From a fossil collecting perspective this means it’s not permitted to extract specimens that are in situ. Collecting efforts should be directed towards the loose boulders and pebbles on the foreshore.

As with all coastal locations, a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

What fossils might you find?

The fossils at Beachy Head are diverse, reflecting a dynamic and changing prehistoric marine environment. Many of the fossil groups are common throughout the various horizons, in particular ammonites, bivalves and sponges. Although ammonites are well documented from the Gault clay and overlying Greensand they are not commonly found and it may take several visits before a specimen is located. We welcome photos of any ammonites in situ within the Gault or Greensand at Beachy Head, please contact us.

The rocks exposed at Beachy Head are dominated by the Chalk and associated flints, and it’s from these respective deposits and concretions that the greatest volume and diversity of fossils can be found. Among the common finds are echinoids, brachiopods, gastropods and bryozoans; less common finds include shark teeth, nautili and crustacean burrows lined with fish scales; on rare occasions belemnites, articulated lobster and fish skeletons, and plant remains can also be found.

Below are a selection of finds made over many visits to Beachy Head. Where possible the specimen’s genus has been indicated below each photo, if a confident ID can’t be achieved a question mark has been added to indicate so.

Above: An event participant holds a squashed Schloenbachia ammonite, West Melbury Marly Chalk.

Above: A split boulder from the West Melbury Marly Chalk contains several Schloenbachia ammonites.

Above: A worn ammonite, encrusted with oyster shells, in situ within the Zig Zag Chalk Formation. The presence of oysters provides evidence that the ammonite’s shell lay exposed on the seabed for a sufficient time for encrusters to colonise its surface. It’s less common to find such a large number in a single association.

Above: A large wave-worn indeterminate ammonite, Glauconitic Marl Member / West Melbury Marly Chalk Formation.

Above: A large Parapuzosia ammonite, Plenus Marls, Zig Zag Chalk Formation.

Above: A unidentified ammonite fragment, found loose on the beach, originally derived from the Upper Gault Clay Formation.

Above: A Eutrephoceras(?) nautilus found within a loose boulder on the foreshore.

Above: A Palaeastacus lobster claw, found within a fallen Lower Chalk boulder. Reducing the matrix will reveal how much of the specimen is concealed.

Above: Jonathan with a gastropod impression, Lower Chalk.

Above: A spiny Spondylus bivalve found on the surface of a fallen boulder, Upper Chalk.

Above: A single ‘Pecten’ bivalve valve in situ on the foreshore, West Melbury Marly Chalk.

Above: A Concinnithyris brachiopod, Zig Zag Chalk.

Above: A flint pebble containing fragments of an inoceramid bivalve shell.

Above: A flint pebble containing fragments of an inoceramid bivalve shell.

Above: An inoceramid bivalve shell on the surface of an air-weathered boulder.

Above: A Cretalamna(?) shark tooth, found within a loose boulder at the cliff base.

Above: A Ptychodus shark tooth, found on the surface of a fallen boulder.

Above: An articulated Beryx fish skeleton, with the top of the skull in cross-section and the vertebrae exposed behind it. Found on a loose boulder, Lower Chalk.

Above: An Echinocorys irregular echinoid encrusted with oysters.

Above: A Micraster echinoid on the surface on an air-weathered boulder.

Above: The internal flint mould on a Micraster echinoid.

Above: The internal flint mould on a Micraster echinoid.

Above: A fragment of Tylocidaris echinoid shell.

Above: A fragment of Tylocidaris echinoid shell.

Above: A Tylocidaris echinoid spine exposed on the surface of an air-weathered boulder.

Above: A Tylocidaris echinoid spine exposed on the surface of an air-weathered boulder.

Above: A bryozoan on an air-weathered surface.

Above: A bryozoan on an air-weathered surface.

Above: A sponge on the surface of a piece of chalk.

Above: A Exanthesis sponge, Glauconitic Marl Member / West Melbury Marly Chalk Formation.

Above: Charlotte with a second sponge in cross-section within a flint pebble.

Above: Charlotte with a second sponge in cross-section within a flint pebble.

Above: A split piece of chalk containing land sourced plant fragments, possibly associated with a dinosaur coprolite (faeces).

Tools & equipment

It’s a good idea to spend some time considering the tools and equipment you’re likely to require while fossil hunting at Beachy Head. Preparation in advance will help ensure your visit is productive and safe. Below are some of the items you should consider carrying with you. You can purchase a selection of geological tools and equipment online from UKGE.

Hard hat: Beachy Head is subject to falling rocks from the cliff-face. It’s a good idea to equip yourself and anyone under your care with a suitable hard hat.

Hammer: A strong hammer will be required to split prospective rocks. The hammer should be as heavy as can be easily managed without causing strain to the user. For individuals with less physical strength and children (in particular) we recommend a head weight no more than 500g.

Chisel: A chisel is required in conjunction with a hammer for removing fossils from the chalk. In most instances a large chisel should be used for completing the bulk of the work, while a smaller, more precise chisel should be used for finer work. A chisel founded from cold steel is recommended as this metal is especially engineered for hard materials.

Safety glasses: While hammering rocks there’s a risk of injury from rock splinters unless the necessary eye protection is worn. Safety glasses ensure any splinters are deflected away from the eyes. Eye protection should also be worn by spectators as splinters can travel several metres from their origin.

Strong bag: When considering the type of bag to use it’s worth setting aside one that will only be used for fossil hunting, rocks are usually dusty or muddy and will make a mess of anything they come in contact with. The bag will also need to carry a range of accessories which need to be easily accessible. Among the features recommended include: brightly coloured, a strong holder construction, back support, strong straps, plenty of easily accessible pockets and a rain cover.

Walking boots: A good pair of walking boots will protect you from ankle sprains, provide more grip on slippery surfaces and keep you dry in wet conditions. During your fossil hunt you’re likely to encounter a variety of terrains so footwear needs to be designed for a range of conditions.

For more information and examples of tools and equipment recommended for fossil hunting click here or shop online at UKGE.

Protecting your finds

It’s important to spend some time considering the best way to protect your finds onsite, in transit, on display and in storage. Prior to your visit, consider the equipment and accessories you’re likely to need, as these will differ depending on the type of rock, terrain and prevailing weather conditions.

When you discover a fossil, examine the surrounding matrix (rock) and consider how best to remove the specimen without breaking it; patience and consideration are key. The aim of extraction is to remove the specimen with some of the matrix attached, as this will provide added protection during transit and future handling; sometimes breaks are unavoidable, but with care you should be able to extract most specimens intact. In the event of breakage, carefully gather all the pieces together, as in most cases repairs can be made at a later time.

For more information about collecting fossils please refer to the following online guides: Fossil Hunting and Conserving Prehistoric Evidence.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it’s your first time fossil hunting or you’re looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more click here.

Page references: A Dynamic Stratigraphy of the British Isles, A. Anderton, P. H. Bridges, M. R. Leeder and B. W. Sellwood, 1992; Geological Conservation Review Series, British Upper Cretaceous Stratigraphy, R. N. Mortimore, C. J. Wood and R. W. Gallois, 2001; Fossil of the Chalk, second edition, A. B. Smith and D. J. Batten, 2002; A Geological Time Scale, F. Gradstein, J. Ogg and A. Smith, 2004; The Geologist’s Association, Stratigraphy of the Upper Cretaceous White Chalk of Sussex, R. N. Mortimore, 1986; www.chalk.discoveringfossils.co.uk. Thanks also to Scott Moore-Fay for his comments and suggestions.