Introduction

Walton-on-the-Naze is a small coastal town in northeast Essex and home to around 6,000 people. The town is bordered along its northern edge by a stretch of rapidly eroding cliffs and foreshore known as The Naze. Erosion has reportedly caused the cliff to retreat 0.5 metres per year in recent years, threatening nearby land and buildings.

Above: The slumping cliff is often visibly mobile. In this photo the sand can be seen bulging ahead of the slumping London Clay and Red Crag.

Above: The slumping cliff is often visibly mobile. In this photo the sand can be seen bulging ahead of the slumping London Clay and Red Crag.

Above: Looking south from near Penny Hole Bay, several trees have recently toppled over the eroding cliff-face.

Above: Looking south from near Penny Hole Bay, several trees have recently toppled over the eroding cliff-face.

The fossiliferous clays and sands exposed in The Naze area belong to the London Clay and Red Crag formations, and provide evidence of prehistoric life and conditions 54 million years ago (mya) and c.2.5 mya respectively. Fossils occur commonly throughout both formations attracting international interest since the 19th century. Above the Red Crag and extending to the cliff-top are several metres of Pleistocene sands and gravels (and recent soil) which although worthy of study, are not the subject of this particular report.

Above: Parking is available at the cliff-top pay-and-display car park alongside The Naze Tower.

Above: Parking is available at the cliff-top pay-and-display car park alongside The Naze Tower.

Above: The Naze Tower – an 18th century Georgian lighthouse.

Above: The Naze Tower – an 18th century Georgian lighthouse.

Access to the beach is made from the cliff-top car park alongside The Naze Tower – an 18th century Georgian lighthouse, now a museum and view point. From the car park a series of concrete steps provide access to the beach and cliff-base. Fossils can be found in either direction of the steps, however the most productive areas occur to the north (left when looking out to sea).

Above: From the car park a series of steps lead down to the beach.

Above: Continuing down the steps, the view north overlooking The Naze cliffs and foreshore.

Above: Continuing down the steps, the view north overlooking The Naze cliffs and foreshore.

The geology of Walton-on-the-Naze

Above: Facing north overlooking the London Clay Formation exposed on the foreshore and in the cliff-face near The Naze Tower.

Above: Facing north overlooking the London Clay Formation exposed on the foreshore and in the cliff-face near The Naze Tower.

Above: The Red Crag Formation exposed near the cliff-top. The overlying paler coloured Pleistocene sands and gravels are visible at the top of the cliff.

Above: The Red Crag Formation exposed near the cliff-top. The overlying paler coloured Pleistocene sands and gravels are visible at the top of the cliff.

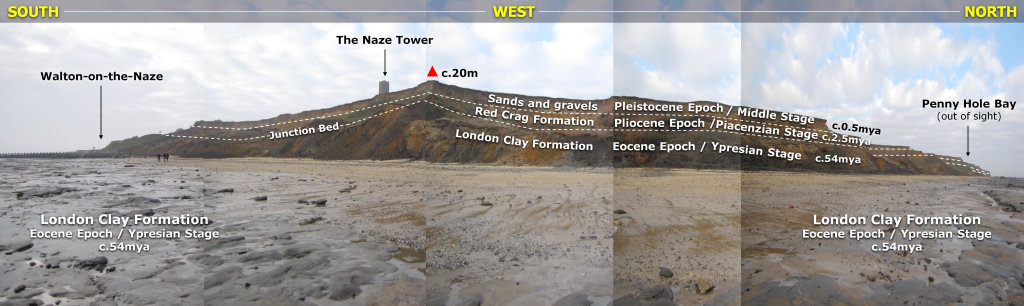

The sediments exposed in situ along the 1.5km stretch of foreshore and cliff between Walton-on-the-Naze and Pennyhole Bay in the north belong to the London Clay and Red Crag formations, and are topped by several metres of Pleistocene sands and gravels (see fig.1 below). Although the Red Crag directly overlies the London Clay at Walton-on-the-Naze it was deposited 51 million years later. The sediment deposited in the interim, which included much of the London Clay, was eroded away and in part contributes to the pebble bed at the base of the Red Crag. This kind of erosive junction between two beds of differing ages is referred to as an unconformity, i.e. the Red Crag unconformably overlies the London Clay.

Figure 1: A geological summary of The Naze cliffs and foreshore as seen in 2010. The extensively slipped cliffs obscure much of the in situ material.

Figure 1: A geological summary of The Naze cliffs and foreshore as seen in 2010. The extensively slipped cliffs obscure much of the in situ material.

The London Clay Formation exposed at Walton-on-the-Naze was laid down beneath a warm, shallow sea during the early Eocene Epoch of the Palaeogene Period, approximately 54 mya, see geologic timescale. For much of this time the nearest significant landmass was perhaps 10-20 miles away. As a result conditions on the seafloor were relatively undisturbed, allowing fine particles of sediment suspended in the water column to gradually settle; however, short-term fluctuations in tidal currents and sea level introduced sand and pebbles to the area throughout this time.

During the Eocene Epoch southern England was located approximately 40°N of the equator, 10°S of its present latitude, comparable to Spain today. The average annual temperature across southern England at this time was approximately 23°C, compared with the present-day figure of around 10°C.

Life during the Eocene was abundant, the nearby land was covered by lush tropical vegetation, providing habitat for mammals, birds and insects, whilst in the sea marine life flourished. The diversity of life is represented in the fossils at Walton-on-the-Naze which includes both marine and terrestrial organisms, the latter consisting of pyritised twigs, fruits and the skeletal remains of birds in particular. To date over 150 bird species had been discovered from the London Clay including forms with teeth, reminiscent of their dinosaurian ancestors.

As time continued to pass the London Clay increased in thickness and was subsequently topped by later marine sediments. However, at some point during the Miocene Epoch 23-7mya, most likely towards the end (prior to the Red Crag’s accumulation), sediment deposition ceased and was replaced by erosive conditions. During this time much of the London Clay and all of the overlying sediments were washed away, leaving the more resistant material behind, e.g. pebbles, phosphatic nodules and robust fossils.

At Walton-on-the-Naze the basal Red Crag pebble bed forms a layer up to several centimetres thick at the horizon marking the onset of the Red Crag’s deposition. This pebble bed is known by many names across the region but for the purposes of this report it’s referred to as the ‘Junction Bed’. The Junction Bed therefore represents material derived from a window of time encompassing much of the London Clay and later sediments. Consequently some of the Junction Bed fossils found loose on the beach today are actually derived from earlier (now absent) sediments. Due to the extensively slipped cliffs at Walton-on-the-Naze the Junction Bed is often obscured beneath loose material.

The position of the Junction Bed represents the end of erosive conditions and return to sediment accumulation – the Red Crag Formation, which occurs unconformably above the London Clay. The Red Crag is a shelly, quartz-rich sand, stained orange with iron oxides. The formation was deposited in a warm, shallow sea (c.20m-30m deep), very close to land around 2.5 mya during the Piacenzian Stage of the Pliocene Epoch, see geologic timescale. The formation contains a large volume of isolated bivalve valves; articulated fossils are rare due to the high energy environment associated with near-shore tidal currents and wave action present at the time.

Where to look for fossils?

The rapidly eroding cliffs and foreshore exposures at Walton-on-the-Naze provide a constant supply of loose material on the beach in either direction of the access point. The stretch of coastline north of the concrete steps and fringed by cliffs is favoured by most visitors; however, the areas of foreshore separated by groins towards the south often proves productive too.

Throughout the year fossils can be found loose on the foreshore as the retreating tide reveals the latest arrangement of beach debris. Shark teeth and pyritised twigs are among the most common fossils from the London Clay, and isolated valves of the bivalve Glycymeris represent the majority of loose fossils from the Red Crag.

Above: Searching for loose fossils eroded from the nearby exposures of London Clay.

Above: Searching for loose fossils eroded from the nearby exposures of London Clay.

Above: A Striatolamia shark tooth found loose on the beach.

Above: A Striatolamia shark tooth found loose on the beach.

At low-tide the London Clay can be observed on the foreshore in situ. The London Clay yields a large volume of pyritised material which accumulates as loose pebbles in narrow channels and holes eroded into the foreshore.

Above: The London Clay Formation observed in situ on the foreshore and in the cliff-face opposite The Naze Tower.

Above: The London Clay Formation observed in situ on the foreshore and in the cliff-face opposite The Naze Tower.

Above: A close-up of the London Clay – a concentration of pyrite pebbles can be seen accumulated in the eroded channel.

Above: A close-up of the London Clay – a concentration of pyrite pebbles can be seen accumulated in the eroded channel.

The upper areas of the cliff provide an opportunity to view the Red Crag in situ, however such excursions are not encouraged due to the fragile nature of the cliffs and access should therefore be limited to study purposes only. The photos below show the Red Crag up close, the downturned valves of the bivalve Glycymeris can be seen protruding the sediment. For those seeking specimens for collection a great number can be retrieved from the slumped material towards the base of the cliff.

Above: The vivid-orange coloured Red Crag Formation, observed in situ towards the cliff-top near The Naze Tower.

Above: The vivid-orange coloured Red Crag Formation, observed in situ towards the cliff-top near The Naze Tower.

Above: A close-up reveals isolated Glycymeris bivalve valves observed ‘downward facing’ within the Red Crag Formation.

Above: A close-up reveals isolated Glycymeris bivalve valves observed ‘downward facing’ within the Red Crag Formation.

As with all coastal locations a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

What fossils might you find?

Below are a selection of finds made over several visits to Walton-on-the-Naze. The best time to visit is during the winter and spring or following stormy weather when the beach has been churned over and new material exposed. Among the common finds include, pyritised wood and fruits, isolated bivalve valves, gastropods and shark teeth.

Above: A sand/wave worn Carcharocles megalodon shark tooth, found loose on the beach, originating from the Junction Bed.

Above: A sand/wave worn Carcharocles megalodon shark tooth, found loose on the beach, originating from the Junction Bed.

Above: A Striatolamia shark tooth found loose among the pebbles on the beach, London Clay Formation.

Above: A Striatolamia shark tooth found loose among the pebbles on the beach, London Clay Formation.

Above: A small unidentified fish vertebra from the London Clay Formation. Found loose among the pebbles towards the top of the beach.

Above: A small unidentified fish vertebra from the London Clay Formation. Found loose among the pebbles towards the top of the beach.

Above: A fragment of whale vertebra from the Junction Bed.

Above: A fragment of whale vertebra from the Junction Bed.

Above: Two unassociated Glycymeris bivalve valves that have come to rest alongside each other. Observed in situ towards the cliff-top, Red Crag Formation.

Above: Two unassociated Glycymeris bivalve valves that have come to rest alongside each other. Observed in situ towards the cliff-top, Red Crag Formation.

Above: An isolated Glycymeris bivalve valve observed loose in slumped cliff material, Red Crag Formation.

Above: An isolated Glycymeris bivalve valve observed loose in slumped cliff material, Red Crag Formation.

Above: The inner surface of a Glycymeris bivalve valve originating from the Red Crag Formation, found loose on the beach.

Above: The inner surface of a Glycymeris bivalve valve originating from the Red Crag Formation, found loose on the beach.

Above: The outer surface of a Glycymeris bivalve valve originating from the Red Crag Formation, found loose on the beach.

Above: The outer surface of a Glycymeris bivalve valve originating from the Red Crag Formation, found loose on the beach.

Above: An isolated valve of an Cerastoderma bivalve from the Red Crag Formation, found loose among slumped cliff material.

Above: An isolated valve of an Cerastoderma bivalve from the Red Crag Formation, found loose among slumped cliff material.

Above: An unidentified gastropod from the Red Crag Formation, found loose on the beach.

Above: An unidentified gastropod from the Red Crag Formation, found loose on the beach.

Above: A Uzita(?) gastropod from the Red Crag Formation, found loose in slumped cliff material.

Above: A Uzita(?) gastropod from the Red Crag Formation, found loose in slumped cliff material.

Above: Two gastropods – Natica (upper) and an unidentified fragment (lower) from the Red Crag Formation, found loose among slumped cliff material.

Above: Two gastropods – Natica (upper) and an unidentified fragment (lower) from the Red Crag Formation, found loose among slumped cliff material.

Above: A Neptunea gastropod from the Red Crag Formation, found loose among slumped cliff material.

Above: A Neptunea gastropod from the Red Crag Formation, found loose among slumped cliff material.

Above: Two children move beach pebbles to reveal a large carbonised tree trunk in situ on the foreshore, London Clay Formation.

Above: Two children move beach pebbles to reveal a large carbonised tree trunk in situ on the foreshore, London Clay Formation.

Above: A pyritised twig from the London Clay, found loose on the beach.

Above: A pyritised twig from the London Clay, found loose on the beach.

Tools & equipment

It’s a good idea to spend some time considering the tools and equipment you’re likely to require while fossil hunting at Walton-on-the-Naze. Preparation in advance will help ensure your visit is productive and safe. Below are some of the items you should consider carrying with you. You can purchase a selection of geological tools and equipment online from UKGE.

Steel point: In some instances it’s not necessary to use a hammer and chisel to remove the matrix surrounding the fossil. Sometimes all that’s required is some careful precision work using a steel point. This is particularly relevant with crumbly matrix, where chiselling may otherwise shatter a fragile fossil.

Hand lens: A hand lens enables the fossil hunter to enjoy the finer details of the specimens they find. It’s often remarkable how well preserved some of the most intricate structures can be. We recommend a lens with x10 magnification that folds away into a metal casing to protect it from damage.

Strong bag: When considering the type of bag to use it’s worth setting aside one that will only be used for fossil hunting, rocks are usually dusty or muddy and will make a mess of anything they come in contact with. The bag will also need to carry a range of accessories which need to be easily accessible. Among the features recommended include: brightly coloured, a strong holder construction, back support, strong straps, plenty of easily accessible pockets and a rain cover.

Walking boots: A good pair of walking boots will protect you from ankle sprains, provide more grip on slippery surfaces and keep you dry in wet conditions. During your fossil hunt you’re likely to encounter a variety of terrains so footwear needs to be designed for a range of conditions.

For more information and examples of tools and equipment recommended for fossil hunting click here or shop online at UKGE.

Protecting your finds

It’s important to spend some time considering the best way to protect your finds onsite, in transit, on display and in storage. Prior to your visit, consider the equipment and accessories you’re likely to need, as these will differ depending on the type of rock, terrain and prevailing weather conditions.

When you discover a fossil, examine the surrounding matrix (rock) and consider how best to remove the specimen without breaking it; patience and consideration are key. The aim of extraction is to remove the specimen with some of the matrix attached, as this will provide added protection during transit and future handling; sometimes breaks are unavoidable, but with care you should be able to extract most specimens intact. In the event of breakage, carefully gather all the pieces together, as in most cases repairs can be made at a later time.

For more information about collecting fossils please refer to the following online guides: Fossil Hunting and Conserving Prehistoric Evidence.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it’s your first time fossil hunting or you’re looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more click here.

Page references: Various species references www.elasmo.com; average annual temperatures across Southeast England, www.metoffice.gov.uk; London Clay Fossils of Kent and Essex, D.Rayner, T.Mitchell, M.Rayner, F.Clouter; Fossil Fishes of Great Britain, D.Dineley and S.Metcalf, Geological Conservation Review Series; British Tertiary Stratigraphy, B.Daley and P.Balson, Geological Conservation Review Series; The Geology of Britain, P.Toghill; Earth Lab Datasite http://www.nhm.ac.uk/jdsml/nature-online/earthlab/index.dsml.