Introduction

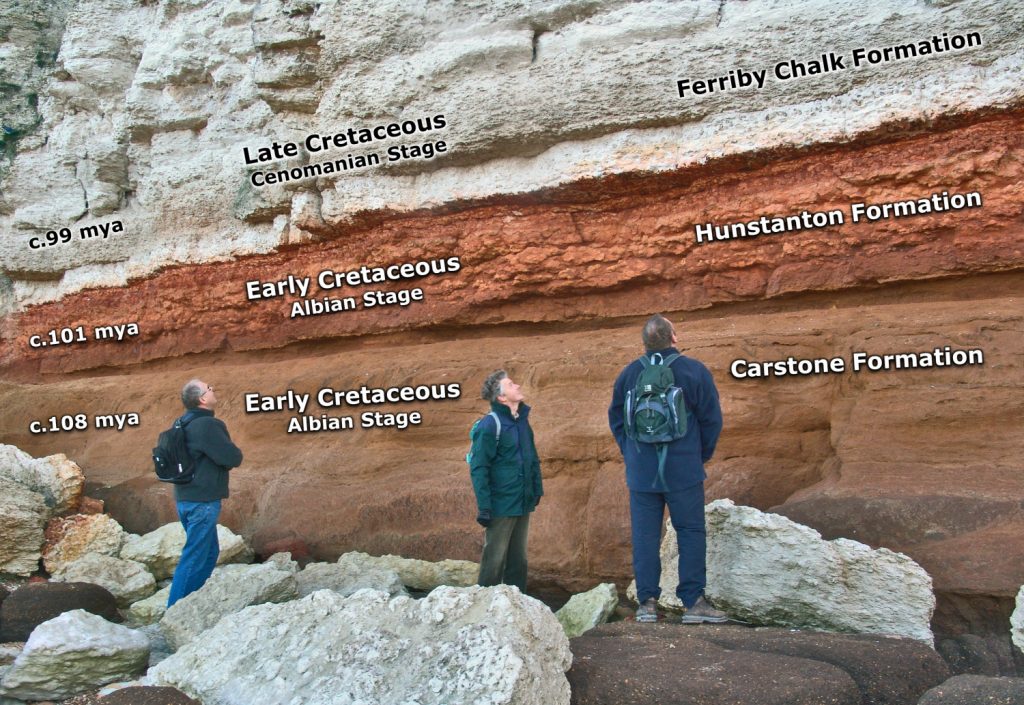

Hunstanton is a small town on the northwest coast of Norfolk and home to approximately 5,000 people. The town is fringed along its western edge by a stretch of dramatic colour contrasting cliffs of orange, red and white sedimentary rocks, reflecting changing depositional conditions towards the end of the Early Cretaceous and the onset of the Late Cretaceous 108-99 million years ago (mya).

Although macro fossils are less frequently encountered within the Carstone Formation, the overlying Hunstanton Formation and Ferriby Chalk Formation are highly fossiliferous and attract significant palaeontological interest. These latter formations contain evidence of a variety of prehistoric marine fauna, including ammonites, belemnites, brachiopods, bivalves, sponges and many other groups.

Access to the beach is made at St Edmond’s Point a short distance north of the ruins of St Edmond’s Chapel and the lighthouse (now a private residence). The coastal footpath traces the cliff-top before descending to beach level a short distance from Old Hunstanton (see photos below). From the access point the cliffs extend south towards Hunstanton.

The geology of Hunstanton

The rocks exposed along the 1.5km stretch of cliff and beach at Hunstanton date from the Albian Stage of the Early Cretaceous Epoch c.108 mya to the Cenomanian Stage of the Late Cretaceous Epoch c.99 mya. The geology features three distinctive formations of marine origin – the Carstone Formation (orange) at the cliff base, followed above by the Hunstanton Formation (red) formerly known as the Red Chalk, and the Ferriby Chalk (white) extending to the cliff-top (see figures 1 and 2 below).

The earliest rock exposed in situ at Hunstanton is the Carstone Formation – an orange (when weathered, otherwise greenish-brown) sandstone deposited during the early to mid-Albian Stage of the Early Cretaceous Epoch. A generalised age of c.108 million years is applied here, however the formation is understood to span a wider window of time.

The Carstone Formation is comprised of coarse sand particles interspersed with rolled pebbles indicative of deposition in a high energy, shallow, near-shore environment with strong currents. Fossils are reported within the Carstone and include rolled ammonite fragments, bivalves and traces of burrowing organisms, though none were observed during the fieldwork undertaken for this report.

Above the Carstone is the Hunstanton Formation a c.1m thick layer of red coloured limestone deposited during the mid-late Albian Stage of the Early Cretaceous Epoch (c.101 mya). Analysis of the Hunstanton Formation in Yorkshire where its thickness increases to c.30m has identified the Early/Late Cretaceous boundary to occur towards its top. For the purposes of this report the formation is assigned wholly to the Early Cretaceous.

The red colouration of the Hunstanton Formation is due to limonite ore and probably reflects the low rate of sedimentation during which oxidisation (rusting) extended into the sea bed. Macro fossils are common throughout the formation in particular belemnites, brachiopods, echinoids and corals.

Resting above the Hunstanton Formation and extending to the cliff-top is the Ferriby Chalk Formation, a white/grey chalk limestone deposited during the Cenomanian Stage at the start of the Late Cretaceous Epoch (c.99 mya). The formation measures c.10m thick locally.

The Ferriby Chalk is largely comprised of the skeletal remains of planktonic algae known as coccolithophores which accumulated to form a white ooze on the seafloor. This soft sediment was later compacted and hardened (lithified) to form chalk – a relatively soft rock itself. The purity of the chalk indicates its formation took place far from land, largely free of terrestrial sands and silts that would otherwise have coloured it.

In comparison with present-day conditions, global sea-levels during the Late Cretaceous were over 200 meters higher. The higher sea levels likely reflect a combination of extreme greenhouse conditions and heightened plate tectonics. Elevated plate tectonic activity and the associated volcanics delivered greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, fuelling the greenhouse effect. Global high temperatures melted much (perhaps all) of the ice at high latitudes, introducing significant amounts of water to the world’s oceans. Uplift of the ocean-floor in regions of active plate tectonics displaced further water onto the continental shelves.

Where to look for fossils?

Much of the in situ chalk at Hunstanton occurs high in the cliff-face and out of reach of visitors, however, natural erosion of the cliff-face provides a fresh supply of fallen material throughout the year, especially during the winter months. These fallen boulders provide productive fossil hunting, with a range of marine fossils visible on the wave and air-weathered surfaces.

As with all coastal locations, a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

What fossils might you find?

A single visit to Hunstanton is sufficient to locate a range of marine fossils, in particular ammonites, belemnites, echinoids, brachiopods, bivalves, sponges, worm tubes, corals and crustacean burrows. Less common finds include shark teeth and occasionally parts of the cartilage skeleton, and fish bones/skeletons. Below are a selection of fossils observed during two visits to Hunstanton.