Introduction

Herne Bay is a small seaside town on the Kent coast, located approximately 9 miles north of Canterbury. The cliffs and foreshore between Herne Bay in the west and Reculver in the east provide an opportunity to explore a prehistoric marine environment dating from 56-54 million years ago. Fossils occur commonly throughout the year especially following stormy conditions when they can be found in large numbers among the pebbles and clay on the foreshore.

Above: View east across the foreshore at Beltinge towards Reculver Towers.

Above: View east across the foreshore at Beltinge towards Reculver Towers.

Above: A fossilised sand tiger shark tooth Hypotodus(?), found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A fossilised sand tiger shark tooth Hypotodus(?), found loose on the foreshore.

The best place to access the beach is at Beltinge – a small suburb of Herne Bay located a short distance east of the town. Parking is available at the end of Reculver Drive from which a concrete path provides access to the beach.

Above: Parking is available at the cliff-top at Beltinge.

Above: Parking is available at the cliff-top at Beltinge.

Above: A concrete path descends from the car park to the beach.

Above: A concrete path descends from the car park to the beach.

Fossils can be found in either direction of the access point, although the most productive areas occur on the foreshore beneath Beltinge and towards Reculver in the east.

As the retreating tide allows access to the foreshore the iconic Reculver Towers can be seen towards the east (shown below). The towers are all that remain of a 12th century parish church that stood within the remains of an earlier Roman fort. The towers continue to provide a visual navigation marker for ships travelling within the Thames Estuary area.

Above: The ruins of Reculver Towers can seen in the distance from the foreshore at Beltinge.

Above: The ruins of Reculver Towers can seen in the distance from the foreshore at Beltinge.

Above: Reculver Towers up-close.

Above: Reculver Towers up-close.

The geology of Herne Bay

The sediments exposed between Herne Bay and Reculver encompass around two million years of history dating from the late Palaeocene and early Eocene epochs of the Palaeogene period, 56-54 million years ago (see geologic timescale). At this time southern England was located approximately 40°N of the equator, 10°S of its present latitude, comparable to Spain today. The average annual temperature across southern England at this time was approximately 23°C, compared with the present-day figure of around 10°C.

The prehistoric evidence reveals Kent (including Herne Bay) lay beneath a warm, shallow sea, the nearest significant landmass was perhaps 20-30 miles away for much of this time. As a result conditions on the seafloor were relatively undisturbed, allowing fine particles of sediment suspended in the water column to gradually settle; however, short-term fluctuations in tidal currents and sea level introduced sand (and pebbles) to the area throughout this time.

Life during the late Palaeocene and early Eocene was abundant, the nearby land was covered by lush tropical vegetation, providing habitat for mammals, birds and insects, whilst in the sea marine life flourished. The diversity of life is represented in the fossils found at Herne Bay which includes both marine and terrestrially sourced organisms, the latter consisting largely of pyritised twigs, seeds and in rare instances insects that were transported by tidal currents.

The earliest deposits belong to the Thanet Formation (Thanetian stage of the Palaeocene epoch) and are best observed on the foreshore and in the cliffs towards Reculver (see figure 1 below). Travelling from east to west the strata dips at a gradient of 3° bringing progressively later (younger) deposits to beach level including the Upnor and Harwich formations, and the London Clay, although the latter is largely obscured beneath sand at beach level.

Figure 1: A geological summary of the cliffs and foreshore between Reculver in the east and Herne Bay in the west.

Figure 1: A geological summary of the cliffs and foreshore between Reculver in the east and Herne Bay in the west.

Fossils occur commonly throughout the various formations, in particular the Beltinge Fish Bed (Upnor Formation) which appears at beach level opposite the access point at Beltinge (below). This fossiliferous bed is the source of many shark and ray teeth, bones and pyritised twigs.

Above: The Upnor Formation clay exposed on the foreshore at Beltinge.

Above: The Upnor Formation clay exposed on the foreshore at Beltinge.

Above: Sandy clay belonging to the Thanet Formation containing fossilised bivalves.

Above: Sandy clay belonging to the Thanet Formation containing fossilised bivalves.

Where to look for fossils?

Fossils can be found loose among the pebbles and clay exposed on the foreshore at low-tide, especially after stormy weather when the rough seas have scoured the beach. If possible it’s best to coincide a visit with a spring-tide when the sea retreats to its greatest extent, exposing areas of the beach that are otherwise inaccessible. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

The most productive area of the beach occurs immediately opposite the access point described and continues for c.100m towards the west. Fossils can also be found towards Reculver in the east where the sand has been swept away and the Thanet Formation is exposed.

Above: Fossils can be found loose among the pebbles and clay on the foreshore (Upnor Formation shown).

Above: Fossils can be found loose among the pebbles and clay on the foreshore (Upnor Formation shown).

Above: A small bag is ideal for teeth and bones.

Above: A small bag is ideal for teeth and bones.

Although fossils are common they’re often difficult to distinguish from the sediment, especially if they’ve been exposed for some time. The photos below demonstrate a typical example, in this instance a partially obscured shark tooth – it’s common for just the tip or root to be visible.

Above: Loose fossils, especially shark teeth (as shown), tend to be obscured by sand and weed. Can you spot it?

Above: Loose fossils, especially shark teeth (as shown), tend to be obscured by sand and weed. Can you spot it?

Above: A sharp eye and patience are required to locate them.

Above: A sharp eye and patience are required to locate them.

What fossils might you find?

The most frequently exposed fossils belong to marine vertebrates, in particular the teeth of Lamniform sharks which hunted in the shallow seas. Although shark teeth occur in large numbers the volume is more reflective of the thousands of teeth a shark may loose in its lifetime. Other fossils include the crushing pallets (usually fragments) of eagle rays, pieces of turtle carapace, twigs, and a variety of benthic fauna including bivalves and gastropods. Below are a selection of finds made during several field trips between Herne Bay and Reculver.

Above: A Striatolamia / Sand tiger shark tooth, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A Striatolamia / Sand tiger shark tooth, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A Striatolamia / Sand tiger shark tooth , Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A Striatolamia / Sand tiger shark tooth , Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: An unidentified partial shark tooth, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: An unidentified partial shark tooth, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A fragment of Myliobatis / eagle ray palate , Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A fragment of Myliobatis / eagle ray palate , Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

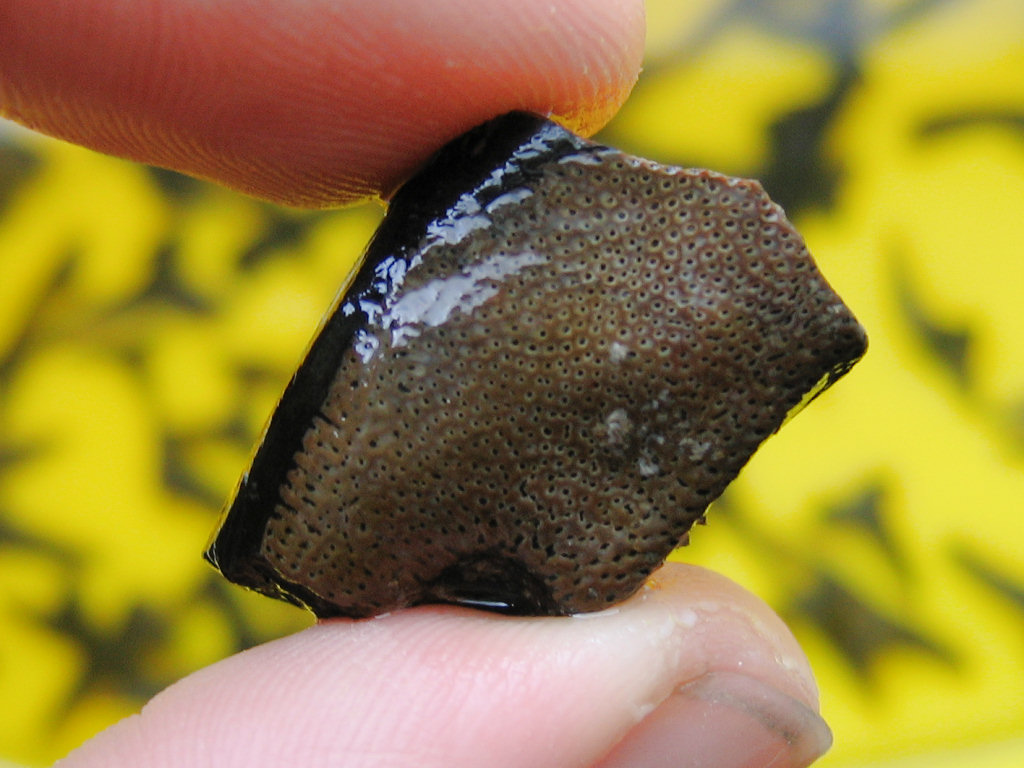

Above: A fragment of Chimaeroid fish dentition Elasmodus(?), Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A fragment of Chimaeroid fish dentition Elasmodus(?), Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A fragment of turtle carapace, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A fragment of turtle carapace, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A partial fish vertebrae, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A partial fish vertebrae, Upnor Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A piece of carbonised wood, Upnor Formation(?) found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A piece of carbonised wood, Upnor Formation(?) found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A pyritised twig, Upnor Formation(?) found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A pyritised twig, Upnor Formation(?) found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A collection of Arctica bivalve shells, Thanet Formation, some in situ and others loose on the foreshore.

Above: A collection of Arctica bivalve shells, Thanet Formation, some in situ and others loose on the foreshore.

Above: A single valve of an Arctica bivalve, Thanet Formation, found in situ.

Above: A single valve of an Arctica bivalve, Thanet Formation, found in situ.

Above: An internal pyrite mould of an Arctica bivalve, Thanet Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: An internal pyrite mould of an Arctica bivalve, Thanet Formation, found loose on the foreshore.

Above: A gastropod shell, Thanet Formation, found in situ.

Above: A gastropod shell, Thanet Formation, found in situ.

Above: A flint pebble (Late Cretaceous Epoch) containing the impression of a regular echinoid spine.

Above: A flint pebble (Late Cretaceous Epoch) containing the impression of a regular echinoid spine.

Tools & equipment

It’s a good idea to spend some time considering the tools and equipment you’re likely to require while fossil hunting at Herne Bay. Preparation in advance will help ensure your visit is productive and safe. Below are some of the items you should consider carrying with you. You can purchase a selection of geological tools and equipment online from UKGE.

Steel point: In some instances it’s not necessary to use a hammer and chisel to remove the matrix surrounding the fossil. Sometimes all that’s required is some careful precision work using a steel point. This is particularly relevant with crumbly matrix, where chiselling may otherwise shatter a fragile fossil.

Hand lens: A hand lens enables the fossil hunter to enjoy the finer details of the specimens they find. It’s often remarkable how well preserved some of the most intricate structures can be. We recommend a lens with x10 magnification that folds away into a metal casing to protect it from damage.

Strong bag: When considering the type of bag to use it’s worth setting aside one that will only be used for fossil hunting, rocks are usually dusty or muddy and will make a mess of anything they come in contact with. The bag will also need to carry a range of accessories which need to be easily accessible. Among the features recommended include: brightly coloured, a strong holder construction, back support, strong straps, plenty of easily accessible pockets and a rain cover.

Walking boots: A good pair of walking boots will protect you from ankle sprains, provide more grip on slippery surfaces and keep you dry in wet conditions. During your fossil hunt you’re likely to encounter a variety of terrains so footwear needs to be designed for a range of conditions.

For more information and examples of tools and equipment recommended for fossil hunting click here or shop online at UKGE.

Protecting your finds

It’s important to spend some time considering the best way to protect your finds onsite, in transit, on display and in storage. Prior to your visit, consider the equipment and accessories you’re likely to need, as these will differ depending on the type of rock, terrain and prevailing weather conditions.

When you discover a fossil, examine the surrounding matrix (rock) and consider how best to remove the specimen without breaking it; patience and consideration are key. The aim of extraction is to remove the specimen with some of the matrix attached, as this will provide added protection during transit and future handling; sometimes breaks are unavoidable, but with care you should be able to extract most specimens intact. In the event of breakage, carefully gather all the pieces together, as in most cases repairs can be made at a later time.

For more information about collecting fossils please refer to the following online guides: Fossil Hunting and Conserving Prehistoric Evidence.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it’s your first time fossil hunting or you’re looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more click here.

Page references: Various species references www.elasmo.com; average annual temperatures across Southeast England, www.metoffice.gov.uk; London Clay Fossils of Kent and Essex, D.Rayner, T.Mitchell, M.Rayner, F.Clouter; Earth Lab Datasite http://www.nhm.ac.uk/jdsml/nature-online/earthlab/index.dsml; Fossil Fishes of Great Britain, D.Dineley and S.Metcalf, Geological Conservation Review Series; British Tertiary Stratigraphy, B.Daley and P.Balson, Geological Conservation Review Series; The Geology of Britain, P.Toghill.