Introduction

Bracklesham Bay has long been one of the most productive and easily accessible locations on the south coast to observe and collect fossils. Throughout the year the sea erodes exposures of fossil bearing clay (mostly offshore), formed during the Eocene epoch around 46 million years ago. Each day, as the tide retreats, a variety of fossils can be found deposited on the sand, including: bivalve and gastropod shells, shark and ray teeth, corals and many other marine fossils.

There are few natural dangers at Bracklesham besides the usual risks associated with a tidal beach. The relatively safe environment makes this stretch of coast an ideal starting point for young families seeking their first fossil hunting experience. Likewise, experienced visitors will find Bracklesham a refreshing change from the usual hammering and digging associated with fossil hunting. Parking, refreshments and toilet facilities are available at the beach access point.

The geology of Bracklesham Bay

The clay formations at Bracklesham Bay belong to a group of sediments called the Bracklesham Group, which extend continuously from West Wittering in the north-west to Selsey in the south-east (see fig.1 below). These sediments were deposited during the Lutetian stage of the Eocene epoch, around 46 million years ago (+/- 1.5 million) by several rivers that supplied sediment into a large estuary connecting to the North Sea. At this time southern Britain lay 40°N of the equator (11° south of its current latitude), equivalent to the present day latitude of Spain. Travelling south-east along the foreshore the exposures become progressively younger.

Throughout the Eocene epoch Britain’s more southerly latitude contributed to a warmer, sub-tropical environment, rich in vegetation and fauna (animal life). Evidence for this is supported by the fossils found at Bracklesham, which include crocodile teeth/bones, turtle carapace, and various land derived seeds and fruits, the latter of which were transported into the estuary by the neighbouring rivers.

From car park at Bracklesham and extending 1 km towards Selsey is the Earnley Formation, a famous clay responsible for the majority of fossils scattered across the sand at low-tide. At certain times of the year large mushroom-shaped pedestals of clay protrude from the sand (below), providing access to fossils in situ (still in the bedrock as apposed to loose on the beach).

For first time visitors to Bracklesham the concentration of the bivalve Venericor and gastropod Turritella (see above-right) is staggering and unlike any other UK location; it’s estimated that the ratio of fossils to clay is as much as 1:3. The Earnley Formation is comprised of 8 numbered beds, with 3 (Venericardia bed) and 4 (Turritella bed) most frequently exposed. The Venericardia bed (shown above) contains abundant double-valved Venericor, whereas the overlying Turritella bed contains a much higher concentration of Turritella gastropods.

Where to look for fossils?

From the car park at Bracklesham fossils can be found in either direction towards Selsey in the south-east (left when facing out to sea) and Wittering in the north-west (right when facing out to sea). Conveniently the greatest volume of fossils tends to be concentrated in close proximity to the car park and for several hundred metres towards Selsey (Earnley Formation – see geology notes above).

Fossil collecting is dependent on a low-tide, which occurs every 12 hours; the low beach gradient provides a brief window of time to collect, before the incoming sea quickly obscures the sand and fossils. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

Beach conditions vary throughout the year and are largely unpredictable. At certain times (particularly during the winter months) the sea transports large volumes of sand away from the beach, exposing the underlying fossil-rich clay. This provides an opportunity to observe fossils in situ. There are also large offshore exposures which ensure a constant supply of loose fossil material throughout the year.

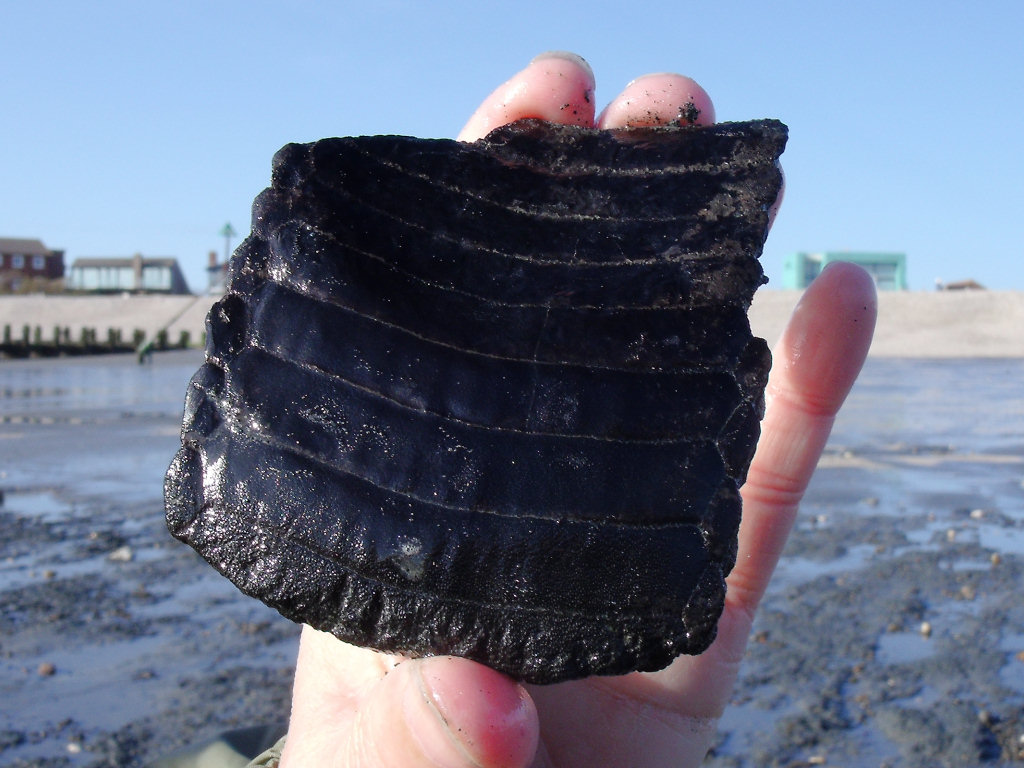

The best place to begin searching for fossils is on the sandy foreshore, in particular around the ends of the wooden breakwaters. At low-tide it’s hard to avoid finding fossils at Bracklesham, although to the untrained eye it’s not immediately apparent which shells are millions of years old and which are modern-day. The most revealing fossil characteristic is the colour: during fossilisation the original colours are lost and the fossil shells takes on a pale-brown, and wood and bone turns black (see below).

An effective technique for locating smaller fossils, in particular shark and ray teeth, is the use of a sieve (see below); this technique is not dissimilar to panning for gold! Certain areas of the beach are more productive than others, in particular keep an eye out for patches of broken shell material on the surface, as this indicates natural grading – a process whereby the sea organises beach material of similar sizes. The smaller the fragments, the smaller the fossils you’re likely to find; likewise the larger the fragments the larger the fossils. The relatively flat beach provides easy access to shallow water in which to sieve the sand and separate the fossils.

Fossils can also be found in situ just a short distance south-east of the car park, although as discussed above, these outcrops are unpredictable and can remain buried beneath sand for several years at a time! On occasions where the sand has been swept away (usually during the winter or after stormy weather) the resulting exposures are worth examining (see below).

Please act responsibly when collecting near the clay exposures and limit the number of specimens recovered to an absolute minimum. There are usually large lumps of loose clay around the base of the pedestals from which to collect; collecting in situ specimens is not recommended and would cause unnecessary erosion to the exposures. Bracklesham is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), which requires visitors observe a code of conduct. If you are not familiar with collecting from SSSIs please visit the Natural Britain website (formerly English Nature).

What fossils might you find?

The fossils at Bracklesham Bay are diverse and represent a complex marine environment and neighbouring landmass. The close proximity to land during deposition is revealed today by the abundance of fossilised wood and fruits contained within the clay outcrops and loose on the foreshore. Fossilised gastropod and bivalve shells are also common, as are shark and ray teeth, fish vertebrae, foraminifera, turtle carapace and crocodile scutes and teeth, although the latter are relatively less so. Below are a selection of finds made over several visits.

Tools & equipment

It’s a good idea to spend some time considering the tools and equipment you’re likely to require while fossil hunting at Bracklesham. Preparation in advance will help ensure your visit is productive and safe. Below are some of the items you should consider carrying with you. You can purchase a selection of geological tools and equipment online from UKGE.

Sieve: A sieve is ideal for filtering smaller fossils from the sand, especially shark teeth which are otherwise extremely difficult to find.

Steel point: In some instances it’s not necessary to use a hammer and chisel to remove the matrix surrounding the fossil. Sometimes all that’s required is some careful precision work using a steel point. This is particularly relevant with crumbly matrix, where chiselling may otherwise shatter a fragile fossil.

Hand lens: A hand lens enables the fossil hunter to enjoy the finer details of the specimens they find. It’s often remarkable how well preserved some of the most intricate structures can be. We recommend a lens with x10 magnification that folds away into a metal casing to protect it from damage.

Strong bag: When considering the type of bag to use it’s worth setting aside one that will only be used for fossil hunting, rocks are usually dusty or muddy and will make a mess of anything they come in contact with. The bag will also need to carry a range of accessories which need to be easily accessible. Among the features recommended include: brightly coloured, a strong holder construction, back support, strong straps, plenty of easily accessible pockets and a rain cover.

For more information and examples of tools and equipment recommended for fossil hunting click here or shop online at UKGE.

Protecting your finds

It’s important to spend some time considering the best way to protect your finds onsite, in transit, on display and in storage. Prior to your visit, consider the equipment and accessories you’re likely to need, as these will differ depending on the type of rock, terrain and prevailing weather conditions.

When you discover a fossil, examine the surrounding matrix (rock) and consider how best to remove the specimen without breaking it; patience and consideration are key. The aim of extraction is to remove the specimen with some of the matrix attached, as this will provide added protection during transit and future handling; sometimes breaks are unavoidable, but with care you should be able to extract most specimens intact. In the event of breakage, carefully gather all the pieces together, as in most cases repairs can be made at a later time.

For more information about collecting fossils please refer to the following online guides: Fossil Hunting and Conserving Prehistoric Evidence.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it’s your first time fossil hunting or you’re looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more click here.

Page references: Alan Morton, www.dmap.co.uk; Ian West, www.soton.ac.uk; David Bone, Geologists Association field notes of Bracklesham; British Tertiary Stratigraphy, Geological Conservation Review Series, B.Daley and P.Balson; The Geology of Britain, P.Toghill. Special thanks to David Bone and Robert Randell for their support and guidance.