Introduction

Barton on Sea is a suburb of New Milton, a coastal town on the south coast of Hampshire, 6 miles east of Bournemouth. The town is home to 23,000 people, many of whom have a heightened awareness of the coastline, if not for its fossils, then for the rate at which it retreats due to erosion, threatening land and properties in the process. Fortunately for the residents the areas considered most valuable/vulnerable are shielded by a series of sea defences, including boulder barriers and planting of vegetation on the slumping cliffs.

The fossils of the Barton Clay are nothing less than spectacular and have interested visitors to the area for centuries. The highly fossiliferous Barton Clay exposed in the cliff between Highcliffe and Barton on Sea provides an opportunity to explore a prehistoric marine environment dating from 40 million years ago. Throughout the year the soft clays and sands are eroded by extreme weather conditions and rough seas, exposing countless fossils in the process, in particular bivalve and gastropod shells, and shark and ray teeth.

Access can be made at either end of the section, although Highcliffe is recommended for its convenience – a large car park and neighbouring restaurant provide parking and refreshments all year round. From the car park a surfaced footpath leads directly to the foot of the cliffs.

Looking across the Solent from Barton on Sea on a clear day the distinctive outline of the chalk Needles and lighthouse can be seen at the western tip of the Isle of Wight. Immediately left (as it appears) of the Needles is Alum Bay, another classic fossil hunting location and a continuation of the Barton Clay discussed below.

The geology of Barton on Sea

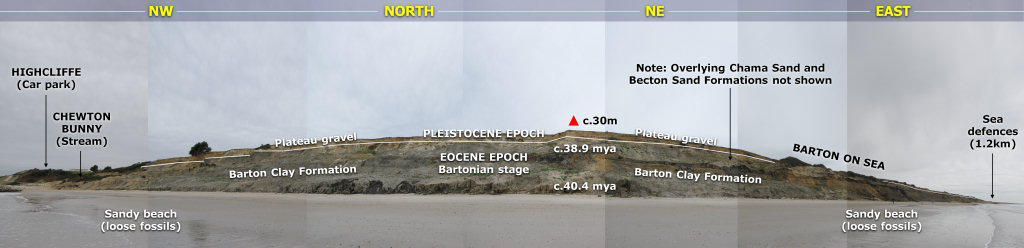

The Barton Clay Formation exposed in the cliffs between Highcliffe and Barton on Sea was deposited at the bottom of a warm (>22°C / 72°F) shallow marginal/shelf sea, relatively close to land, during the Bartonian stage of the Eocene epoch, approximately 40.4 – 38.9 million years ago (see geologic timescale). At this time southern Britain lay 40°N of the equator (11° south of its current latitude), equivalent to the present-day latitude of Spain.

The Barton Clay measures approximately 30m thick and is one of three formations belonging to the Barton Group exposed in the cliff. Overlying the Barton Clay is the Chama Sand (5.5m) and Becton Sand (22m), together the three formations measure approximately 60m, although no more than 30m is exposed at any given point. Neither of the latter formations are the subject of this report, however it should be noted that the Chama Sand appears towards the top of the cliff, close to where the above panoramic was taken, and descends gradually as the beds dip eastward. The overlying Becton Sand appears at the top of the cliff a short distance from the sea defences to the east. The cliff-top is capped by up to 5m of Pleistocene gravels, deposited around 800,000 years ago.

The Barton Clay Formation includes both sand and clay to varying degrees in each of the ten beds which make up the formation, representing shallow/near-shore and deeper/off-shore conditions respectively. The varying composition reflects the changing sea levels and proximity to land throughout this time. The presence of sand is indicative of a high energy environment, in this instance the coastline, and accumulates to a greater extent relatively close to its source. During periods of regression (falling sea levels) the shallowing sea forced the coastline seaward and closer to the Barton area, delivering a greater volume of sand to the area. Clay on the other hand (formed of silt/mud) is indicative of a deeper, low energy setting – the finer particles are able to remain suspended within the water and travel a greater distance from their source, before settling to the sea floor. During periods of transgression (rising sea levels) the coastline was pushed inland, reducing the supply of sand to the Barton area and favouring the accumulation of silt/mud.

The fossils of the Barton Clay reveal a diverse marine and neighbouring terrestrial ecosystem, the latter of which is evidenced by fossilised plant material – mostly drift wood. However it’s the marine mollusc fauna which attracts the most attention, in particular the shells of gastropods, bivalves and scaphopods (see example fossils below). These fossils provide evidence of a benthic mollusc fauna consisting of many hundred of species.

Where to look for fossils?

Fossils can be found along the entire stretch of coast between Highcliffe and Barton on Sea, however the Barton Clay is best represented towards the former, where a near complete sequence is exposed in the slumping cliffs. Travelling east the gently dipping beds become progressively obscured below beach level, simultaneously providing access to the overlying formations.

At Highcliffe access to cliffs can be made with ease, indeed fossils occur in high concentrations in the seaward end of the slumped Barton Clay, so it’s not necessary to travel far to find a diversity of fossils. Close inspection of the Barton Clay reveals a mass of broken fossil material alongside plenty of complete specimens too, especially gastropods. Throughout the year the sea and rain erodes the soft clay, leaving the fossils protruding from the surface and loose on the beach.

As with all coastal locations, a fossil hunting trip is best timed to coincide with a falling or low-tide. For a relatively low one-off cost we recommend the use of Neptune Tides software, which provides future tidal information around the UK. To download click here. Alternatively a free short range forecast covering the next 7 days is available on the BBC website click here.

What fossils might you find?

Below are a small selection of fossils discovered within (or originating from) the Barton Clay. Due to the slumping nature of the cliffs, much of the apparently in situ material is no longer so, making the task of identifying the bed name/letter a challenge. Consequently for the purposes of this investigation, all fossils are simply assigned to the Barton Clay Formation and are only indicated as in situ where it was reasonably apparent.

Where possible the genus of each specimen has been indicated, if a confident ID can’t be achieved a question mark has been added to indicate so. Among the more frequent finds include bivalve, gastropod and scaphopod shells; less frequent finds include shark and ray teeth, fish bones, and pieces of turtle carapace, although following periods of stormy weather the frequency of finds can increase significantly.

Tools & equipment

It’s a good idea to spend some time considering the tools and equipment you’re likely to require while fossil hunting at Barton on Sea. Preparation in advance will help ensure your visit is productive and safe. Below are some of the items you should consider carrying with you. You can purchase a selection of geological tools and equipment online from UKGE.

Steel point: In some instances it’s not necessary to use a hammer and chisel to remove the matrix surrounding the fossil. Sometimes all that’s required is some careful precision work using a steel point. This is particularly relevant with crumbly matrix, where chiselling may otherwise shatter a fragile fossil.

Hand lens: A hand lens enables the fossil hunter to enjoy the finer details of the specimens they find. It’s often remarkable how well preserved some of the most intricate structures can be. We recommend a lens with x10 magnification that folds away into a metal casing to protect it from damage.

Strong bag: When considering the type of bag to use it’s worth setting aside one that will only be used for fossil hunting, rocks are usually dusty or muddy and will make a mess of anything they come in contact with. The bag will also need to carry a range of accessories which need to be easily accessible. Among the features recommended include: brightly coloured, a strong holder construction, back support, strong straps, plenty of easily accessible pockets and a rain cover.

Walking boots: A good pair of walking boots will protect you from ankle sprains, provide more grip on slippery surfaces and keep you dry in wet conditions. During your fossil hunt you’re likely to encounter a variety of terrains so footwear needs to be designed for a range of conditions.

For more information and examples of tools and equipment recommended for fossil hunting click here or shop online at UKGE.

Protecting your finds

It’s important to spend some time considering the best way to protect your finds onsite, in transit, on display and in storage. Prior to your visit, consider the equipment and accessories you’re likely to need, as these will differ depending on the type of rock, terrain and prevailing weather conditions.

When you discover a fossil, examine the surrounding matrix (rock) and consider how best to remove the specimen without breaking it; patience and consideration are key. The aim of extraction is to remove the specimen with some of the matrix attached, as this will provide added protection during transit and future handling; sometimes breaks are unavoidable, but with care you should be able to extract most specimens intact. In the event of breakage, carefully gather all the pieces together, as in most cases repairs can be made at a later time.

For more information about collecting fossils please refer to the following online guides: Fossil Hunting and Conserving Prehistoric Evidence.

Join us on a fossil hunt

Discovering Fossils guided fossil hunts reveal evidence of life that existed millions of years ago. Whether it’s your first time fossil hunting or you’re looking to expand your subject knowledge, our fossil hunts provide an enjoyable and educational experience for all. To find out more click here.

Page references: Special thanks to Alan Morton for his assistance identifying the specimens featured. For a detailed study of the fossils of the Barton Clay please visit Alan’s website: www.dmap.co.uk/fossils; Ian West’s website for geological references and field trip planning: click here; Fossils, C. Walker, D. Ward; www.en.wikipedia.org various references; A Geological Time Scale, F. Gradstein, J. Ogg and A. Smith, 2004; Atlas of Palaeogeography and Lithofacies, The Geological Society Memoir No. 13, J. C. W. Cope; Geological Conservation Review Series; British Tertiary Stratigraphy, B.Daley and P.Balson.